|

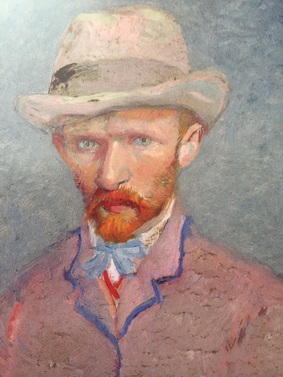

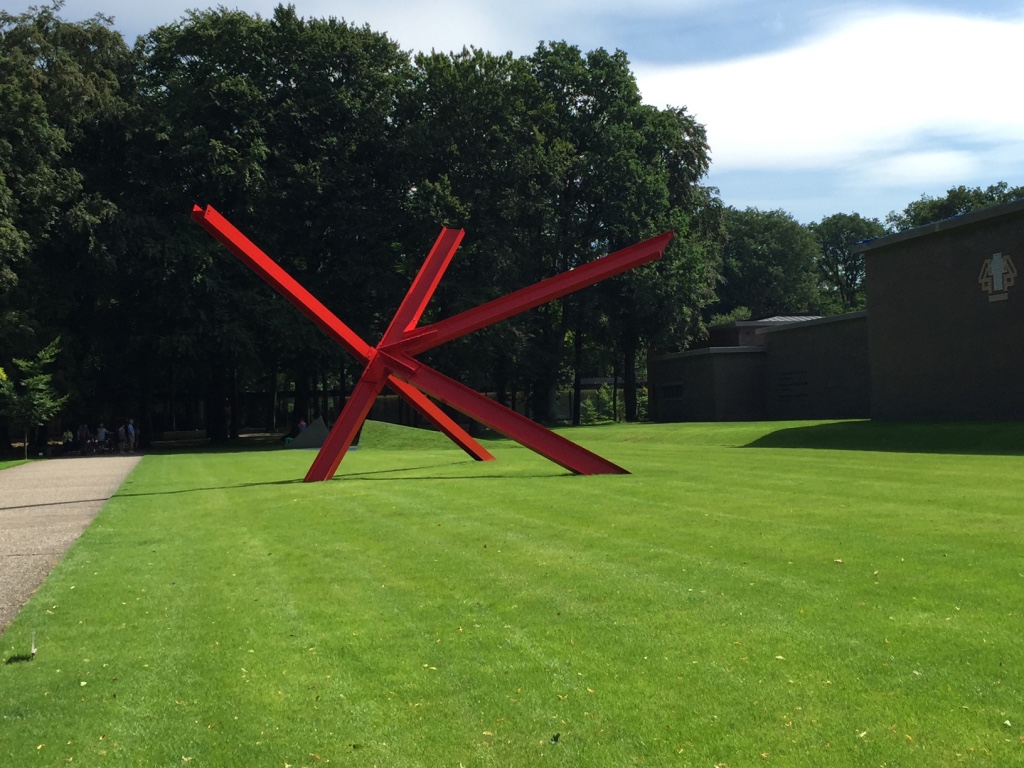

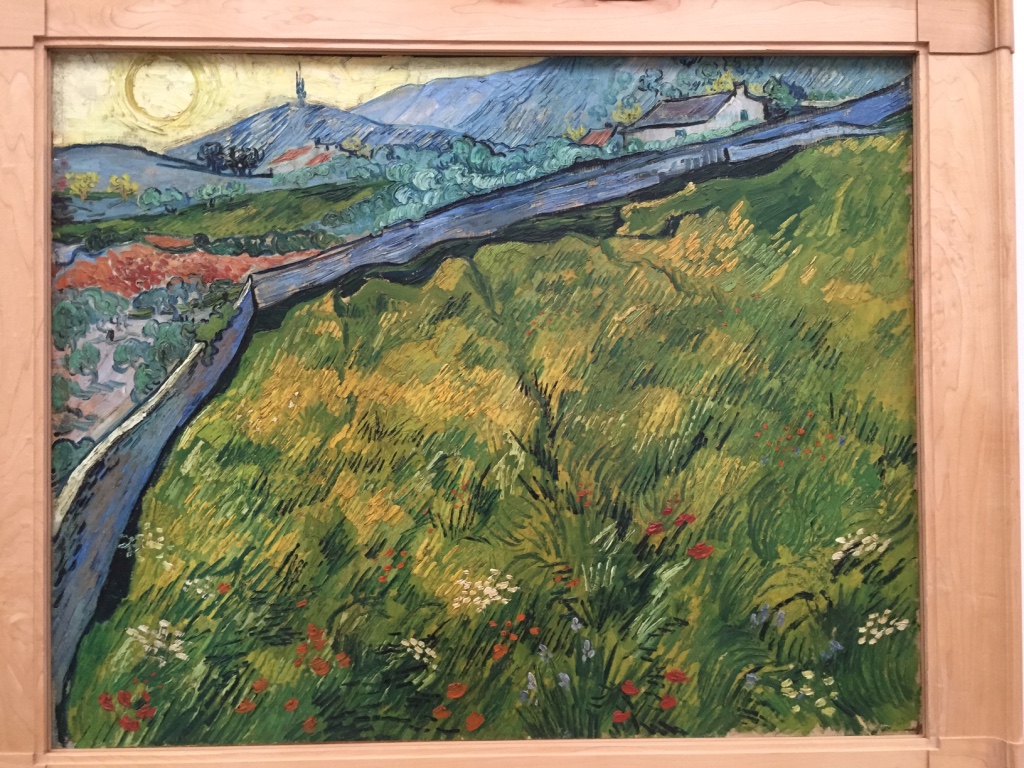

10th August, 2016 There is, at last, more time to write as I am on a plane again, this time departing from Schipol Airport, Amsterdam and flying to Geneva to see family in Yverdon. The thing I enjoy about flying in Europe is the complete absence of safety videos with an All Blacks theme. I dislike them. I find them corny and pointless. The only segment of an Air New Zealand instructional film that appeals to me is the footage of the kiwi surfer Ricardo Christie. I like his blue eyes and his shoulder length, wavy, blonde hair and the way he smiles broadly, as the four wheel drive he is steering bounces over a dirt track by the sea. Here on this plane, there is no screen, just lovely KLM flight attendants, a woman with a blonde chignon and a Dutch African man with black ringlets. They stand in the aisle, bracing their legs, and demonstrate how to open and close a seat belt and pull down on the oxygen mask which might be all you could achieve in a sudden emergency, apart from that highly televised miraculous landing in 2009, after the US pilot, captain Chessley Sullenberger, flew into a flock of birds that then jammed the jet engines forcing him to float his plane down onto the Hudson River. I remember the scenes of the plane on the water, and the people huddled together on the wing, before the rescue boats arrived. It was the happiest story to emerge from New York in a long time. Yesterday because of a silly human error, the experience of the Kröller Müller sculpture park and art collection, half way between Hummelo and Amsterdam, was marred. We had forgotten to empty the safe at the Bed and Breakfast. It was located at the bottom of a kitchen cupboard behind a rubbish bin and I remember having had had an earlier discussion about whether to use it or not. We must have put the valuables inside and then promptly forgotten about them. When you’re travelling through Europe on fast-forward, you really can forget your head. In the car I had said, in a self-satisfied way, to Cleo, that on my last survey of the bedroom, I had lifted the lid of the brown and cream wicker woven laundry basket and my pacific island necklace, a brown and white shell on a cocoa-coloured woven cord made by my friend, Sofia Tekela-Smith, had dropped to the floor. Wasn’t that lucky,’ I remarked to Cleo. Alas, arriving at the sculpture park, I opened my backpack, looked into the apricot cavity and thought something is not right. My little jewellery pouch was missing along with the passports. This meant that a journey that should have lasted a pleasant two hours, with a break at the sculpture park in the middle, turned into a four hour trip all up, three of them after our time at the park. Luckily we were both at fault in this instance and there was no blaming. The brilliant thing about the Kröller Müller experience is that the museum and sculpture park are located in the Hoge Veluwe National park, a vast area of forest and wide open spaces patterned with low growing grey firs, like Christmas trees and the yellow wild flowers of golden rod. The grass there is burnt off and pale brown, reminding me of the landscape around the Rakaia riverbed in Canterbury in the summertime, although there the flora is gorse, broom and lupins and the fauna is rabbits. The only access to the museum is across the park, along a 2½ kilometre long cycleway. There were hundreds of bicycles to choose from, at the park entrance, big, comfortable jalopies with wide seats, and pedal brakes. I haven’t been on a bicycle in years and the feeling as I went freewheeling through the trees was a revelation. As the wheels spun I was reminded of the female physician in the German film Barbara riding through wartime East Germany, near the Baltic Sea. And rolling further back I was a girl again, on the Canterbury Plains, riding my bike, with my dress winding up round my thighs and not caring and with the wind rushing through my hair. I sensed that other cyclists, on this path, on a beautiful Sunday afternoon in The Netherlands shared the feeling. It wasn’t expressed necessarily in smiles but rather in a softening around the mouth and jawline. There were people from many nations crossing the park, from Africa, China, Japan, Europe, the US, each individual discovering and delighting in the fact that they still knew how to ride. This is something I admire about the Dutch, the way they privilege the bicycle. The whole country is criss-crossed by cycle-ways, so that as you drive through the landscape, you see young people, middle-aged couples, the elderly, moving seamlessly, with just their torsos showing, above the summer pastures. The Dutch do seem more relaxed. And then someone up ahead spotted, in the distance, the faint outline of a baby deer, and braked suddenly so that all the people following close behind almost fell off their bicycles. There is something for everyone at the Kröller Müller art museum and sculpture park— there is the steel pivot, K piece by Mark di Suvero its bright red colour set against the shiny green lawn near the entrance to the gallery, there is the essence of swan Sculpture Fotent 2 by Marta Pan sailing in a dark pool beyond the galleries and inside, hanging from a glass panelled ceiling, there are the matte soft red blades of an Alexander Calder mobile The vast painting collection once belonged to Helene Kröller Müller (1869 – 1939). She was one of the first women anywhere, to gather a major collection of art including paintings by the Impressionists and Pointillists and a major collection of the work of Dutch artists right up to the 1930s. She was also one of the first to recognise Van Gogh’s brilliance and she was generous and foresighted. In 1935 along with her husband Anton Muller she donated the entire collection along with their large forested estate to the Dutch people.  A woman baking bread (1854) by Jean-Francois Millet A woman baking bread (1854) by Jean-Francois Millet At this gallery I viewed the collector’s favourites, Odilon Redon and Camille Pissaro, Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg and Charley Toorop and one very beautiful Jean-Francois Millet painting, Peasant Woman Making Bread (1854). She is painted from behind, wearing a white shift and soft blue-green dirndl, with a terracotta apron. There were many Van Goghs on display; thrilling landscapes, a painting from his almond blossom series and one lovely painting of sunflowers, quite different from the better known gold and ochre works, where the small brushstrokes were like multi-coloured threads in a tapestry. Writing to his brother, Theo, the artist Vincent Van Gogh said of his sunflower paintings, 'You know that the peony is Jeannin's, the hollyhock belongs to Quost, but the sunflower is somewhat my own." The collection of works in the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam is larger of course, and the paintings are intelligently organised and beautifully displayed, often on walls painted in his famous turquoise. It’s a very special thing to come upon an entire museum, containing hundreds of works devoted to one artist. It gives the viewer an opportunity to really get to grips with the scale of the artist's oeuvre and the phases of artistic development. The museum is a tribute to Van Gogh, made possible by the efforts of Theo’s wife, Johanna Van Gogh-Bonger and their son Vincent Willem who promoted his work, after the deaths of Vincent and then Theo, although it’s a bittersweet achievement because the public recognition arrived too, too late to save the artist.  I had forgotten that Van Gogh was mostly self-taught, learning through study of the Old Masters, making drawings after prints of their works. On close inspection I found the early paintings, especially of peasants and his still-life compositions surprisingly unremarkable. At the Kröller Müller museum there are five of his paintings of birds’ nests exhibited side by side and they are black. The form is indistinguishable. It could be a Malevich black painting, or a smoke damaged Caravaggio. This set me wondering about his learning process. What was it that assisted his progress from the sombre early paintings to the vibrant, pulsating and throbbing imagery of his later work? The answer, I think resides in his responsiveness to learning, from other artists, particularly and his willingness to experiment and through acute observation of Nature. In 1881, at the age of 28, Van Gogh studied art with his cousin by marriage, Anton Mauve, of the Hague School of painters, and later in 1885 he attended art school in Antwerp but quarrelled with his teachers and broke away. Initially he followed the 19th century realist painters, Jean-Francois Millet, Jules Breton and Jozef Israels and painted peasant life, casting them as ennobled individuals at work, but it was in Paris, where he lived with his brother, the art dealer Theo, that he encountered the work of the Impressionists and the Pointillists, and was especially inspired by the paintings of Corot, Degas, Pissaro, Toulouse-Lautrec and Gauguin and also the Japanese woodcuts by Hiroshige. This was the moment when his painting underwent a major transformation and his palette changed dramatically, turning lighter, brighter and gradually more bold. There is a painting of a kingfisher where you can see the genius beginning to show in the acute and refined rendering of the bird form and in the jewel-like colours. Quite often artists can write as well as paint and it is always illuminating to read their descriptions of their art practice and what it is they see, especially in Nature. This is how Van Gogh describes his house in Arles to his sister Willemien, My house here is painted outside in the yellow of fresh butter, with garish green shutters, and it’s in the full sun on the square, where there’s a green garden of plane trees, oleanders, acacias. And inside, it’s all whitewashed, and the floor’s of red bricks. And the intense blue sky above. Inside, I can live and breathe, and think and paint. Letter to to Willemien, Arles, 9 and 14 September 1888 Walls that are ‘yellow like fresh butter,’ such an apposite description. He describes the colour of the Mediterranean as like ‘mackerel’ by which he means always changing ‘you don’t always know if it’s green or purple — you don’t always know if it’s blue — because a second later its changing reflection has taken on a pink or grey hue.’ Letter to Theo Van Gogh, Les- Saintes-Msries-de-la-Mer, 3 of 4 June. Recently I watched a documentary about Van Gogh, where the juxtapositions of his paintings and the cinematography of the light on the landscape of Arles awoke me to the wonder of his work and especially to his daring colour palette; sulphur, magenta, emerald, cobalt. Years ago I visited the Van Gogh Museum as a twenty-one-year-old graduate with a BA in Art History taught by the inspirational Jonathan Mane-Wheoki and Julie King. On that visit I think I viewed the work in a more studious way following the progression of the modern art movements at the turn of the 19th and 20th century, slavishly contemplating every single work and delighting in seeing the actual paintings, after three years of colour slides of reproductions projected on a screen in a darkened lecture hall. But now when I view art, I gravitate to the modern period and the artists I like and approach the work from a more emotional place, responding especially to colour and mood.  Self-portrait' (1887) by Vincent Van Gogh. Self-portrait' (1887) by Vincent Van Gogh. The narrative of Van Gogh’s life and work is an unhappy one. He was the unconventional child in a large family and was unlucky in love. His affair with a prostitute brought shame to his family and especially his father, Reverend Van Gogh. Vincent Van Gogh was 31 when his father died suddenly, from a stroke, and the relationship obviously didn’t have a chance at healing. He worried also about money, this was a perennial problem, and was completely dependent, financially, on his brother Theo. In his lifetime Van Gogh received only a little recognition and at the time of his death he was despairing over whether his art mattered. In a gallery at the bottom of the beautiful Rietveld designed building, I viewed a temporary exhibition entitled ‘On the Verge of Insanity’. It was presented like an anatomy of mental illness that painstakingly traced the steps upon Van Gogh’s path to his suicide in 1890. I was both drawn to the discussion and repelled. There was, for example, a replica of the pistol he shot himself with in a glass case that I found unnecessary. On one wall though there was a chart of the very many medical and psychological theories that have been postulated on the causes of his insanity in the years since his death. I thought it read like a history of psychoanalytic theory, but I’ve lost my notes and can’t remember many of the conditions now. Some were very unlikely such as Menieres disease, a constant ringing in the ears, although maybe that helps to explain why he cut off part of his ear, after the quarrel with Gauguin because the persistent buzzing can be maddening. Nobody really knows why he did that. There was a suggestion of alcoholism but the most likely diagnosis was bi-polar disorder because he seems to have swung from periods of ecstasy when he was painting Nature and it was going well, to deep despondency when he worried about money and whether his painting was of any value. My theory is that his periods of incarceration in the mental asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence frightened him and added to his anxieties, although conditions were made slightly tolerable when his doctor allowed him to paint — a privilege that was removed for a period when he swallowed the paint in an attempt at suicide. There were no alternatives in the 19th century but the thought of incarcerating a deeply sensitive and tortured artist in a hospital in the company of other suffering, possessed and very ill people seems harsh and counterproductive. Each time Van Gogh was readmitted he lost confidence in his ability to ever recover and be well again.  For me the final stages of this exhibition were profoundly sad. His final known painting, Tree Roots, 1890, was executed when his mind was collapsing and the imagery is fractured and distorted and the colours are dull. It just hasn’t worked. And then still sadder were the displays of obvious courage as he battled his mental illness exerting extreme willpower to keep on painting. During his hospital stays he asked for prints of paintings by the Masters and made his own paintings after them including a beautiful interpretation of a painting by Delacroix. He also painted the view of the hospital gardens and the landscape beyond seen through the grille over the window in his cell. Enclosed Wheat Fields with Rising Sun was painted from this vantage point in late May 1889 just months before his death

1 Comment

13/8/2016 08:07:45 pm

Very beautiful and inspiring writing and descriptions. I found it deeply evocative and full of fascinating insights and information. Very much enjoyed it! Thank you, Deborah!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed