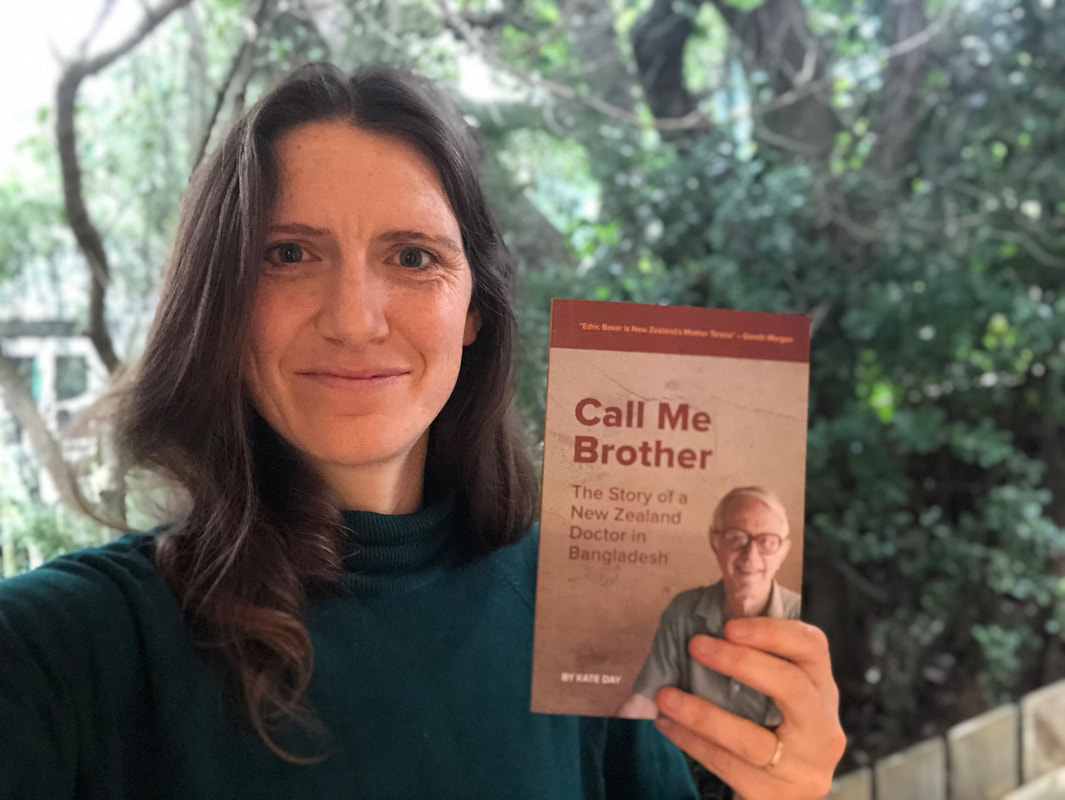

What happens when one person refuses to tolerate injustice and gives everything they have to seeing it right? Dr Edric Baker was driven by the idea that healthcare should be available for every person, rich or poor. His vision was sparked by a wartime experience in Vietnam, where he’d performed complex surgery on a patient, only to see him return and die from dysentery, a disease of poverty. Undaunted by the magnitude of his aspiration he refused to accept that healthcare was out of the reach of the poor and devoted his life’s work to finding an alternative. I am delighted to profile this beautifully written new biography Call Me Brother: The Story of a New Zealand Doctor by Wellington writer Kate Day. In 2020 I was approached by Kate for a manuscript assessment and then when the final draft was completed I worked on the final edit. Throughout it was a pleasure to be involved with this first-time author who had a natural facility with the written word. Edric Baker's story is inspiring, as is the story behind the creation of this book. Below Kate addresses a series of questions about the origins of the project, the book's themes, her research and writing process, the publishing journey and some high and low points along the way. Call Me Brother: The Story of a New Zealand Doctor is the story of a remarkable man who journeys from peaceful New Zealand to wartime Vietnam where he was imprisoned by the Viet Cong, to Kailakuri a rural settlement in Bangladesh, where he pioneered a ground-breaking model of healthcare for the poor. Kate Day’s biography tells the story of that thirty-five year crusade where sustained by his Christian faith, he set about addressing the 'emergency of poverty’. Living in extreme simplicity alongside the people he sought to help, Baker developed a system for treating diabetes and providing basic healthcare at extremely low cost. By partnering with the people best-suited for the task — the poor themselves — he established and grew the Kailakuri Healthcare Project to a team of ninety staff, most without formal qualifications, who now serve 28,000 patients per year. His work has dramatically changed the lives of thousands and for that he is affectionately known in Bangladesh as the nation's ‘Doctor Bhai’ meaning 'Doctor Brother'. An irresistible project Tell me about the origins of this project Kate? In 2012, while I was studying at Canterbury University, a man named Edric Baker spoke at my church. At that talk I learned he was a kiwi doctor who lived in the remote village of Kailakuri in Bangladesh and over three decades had trained local people to provide medical care. On this visit to New Zealand he was raising funds for the Kailakuri healthcare centre, his team and patients. The work helping diabetics manage their condition was achieved on a shoestring, treating each outpatient for less than two New Zealand dollars, and helping diabetics manage their condition for just a few cents per day. The exceptional work had led philanthropist Gareth Morgan to call Edric Baker, ‘New Zealand’s Mother Teresa’. After the talk I had an unshakeable conviction that I had to interview Edric before he left New Zealand. When I phoned to request an interview, he apologised saying there was no time before his departure for Bangladesh. And then he paused and said, “Except… tomorrow I will be on a bus from Paraparaumu to Auckland. If you can get on the bus you can interview me.” I flew to Wellington immediately, boarded a bus the next morning, which fortunately was the same bus that Edric boarded at Paraparaumu. I spent the ten-hour journey recording my interview with Edric on my audio recorder. Then we parted ways in Auckland. Afterwards I wrote up the interview, sent it off to his organisation, and moved on with my life. Three years later in 2015 I heard that Edric had died. The following year, I made a new year’s resolution to get into writing. On 2 January 2016, out of the blue, his organisation emailed asking if I might write Edric’s biography. I felt God nudging me. Eventually, I said yes. So began a six-year project. What were the main themes around which the biography pivoted? Edric’s life posed deep questions that I wanted to answer. What makes a person go ‘all in’ to pursue an ideal? As a young doctor working in Vietnam, Edric had seen people die for lack of basic healthcare. That was an injustice Edric simply could not tolerate. His answer to the challenge was to train local people - many without formal schooling - as paramedics to serve their own community. I wanted to know how he’d made that model work and could it be replicated elsewhere? I wondered also how Edric had sustained himself and remained true to his vision for so many years despite setbacks, failures and even problems generated by his own personal struggles. In a letter to his family in September 1983, from the site of his fledgling healthcare centre he wrote: What I am trying to do here is to show that it is possible to treat most common illnesses at almost no cost – with community support. It is slow and extremely frustrating, especially the lack of interest of our committee and community and church leaders. They got quite a shock a few days ago when I told them I was going to leave in the next two or three days! I was ready to too. Then we had a committee meeting and sorted things out. He wrote to his sister about his choice to live in radical simplicity: No doubt most people think my way of life is just madness but it is based on a conviction and a belief, and in its better moments on a love – and it’s too late to change it now… Tell me about your research process, the interviews and your archival searches? Altogether I interviewed several hundred people. The first round of interviews were a mixture of in person or via phone around New Zealand. I later travelled to Bangladesh and Vietnam. I also read thousands of documents, including letters kept by family members, friends and colleagues. Fortunately Edric was a keen letter writer throughout his life, and people had held onto his letters and were happy to share them with me. How would you describe the writing process, the timeframe and something about the optimum conditions for writing? I wrote the book over many years. At first I spent periods full time on the project, then part-time alongside other work. After having children I could write only during writing retreats at my parents’ place in Christchurch while they supported me with childcare. When the writing was flowing it felt brilliant, like I was weaving the threads of my research into a tapestry that had form and shape! Congratulations, your book is now published and I understand it is being translated into Bangla for publication in Bangladesh. How did you navigate the publication process? We spent about a year pitching to publishers and eventually found an American publisher willing to take it on. Once we viewed the contract however, we realised there was a problem. We wished to translate the book into Bangla (the Bengali language) and to sell it in Bangladesh. If we signed over the rights of the English version to an American publisher, they would hold the rights to any translation, and receive a cut of proceeds when that version later sold in Bangladesh. This didn’t feel right. We were concerned about the financial viability for a Bangladeshi publisher under these contractual obligations. We decided to publish the book ourselves. We found an amazing cover designer and typesetter, Emma Bevernage; our own proofreader; and (after a long search) a printing house in Dhaka. Mebooks did the e-book conversion. Meanwhile, we found a Bangladeshi translator and we are now in conversation with Bangladeshi publishers who may take on the project. Do you have a high moment and a low moment you would like to share? There have been many high moments. A standout period was visiting Kailakuri and interviewing Edric’s colleagues and patients. Speaking to people via an interpreter is a thrilling experience. In effect they threw out a bridge that connected us, enabling a conversation that would otherwise be impossible. I have such respect for interpreters. A low moment came at the beginning of the self-publishing process. I was focussed on parenting and felt ready for the book project to be over! But I realised there were still enormous amounts of research and decision-making ahead. Bit by bit, we got there, and I’m pleased with the result. Book extract Edric arrives in Vietnam in 1969 with the New Zealand Surgical Team: When it came to the technical aspects of surgery, Edric was on a rapid learning curve. With Jack as a mentor, he learned to improvise with basic equipment and to manage a whole new variety of injuries. This was surgery such as Edric had never encountered in New Zealand. There, patients would arrive at hospital quickly, with injuries that were clean, and survival was expected. In Vietnam it was the opposite. Patients could arrive a day or more after injury. Infection was expected; survival was not. This was no context for the meticulous examinations that had backed up the Wellington Hospital emergency department. In Qui Nhon Edric learned to compromise to keep up with the injury toll. While the war injuries were horrific, Edric also noticed the ailments that resulted from poverty. Accidents on potholed roads were common, as were burns from fires in thatched huts, all adding to surgery queues. Then there were patients at risk of death from malnutrition, cholera or other preventable disease. ‘Poverty is a state of emergency,’ Edric realised, and would later write, ‘Just as in a time of war a state of emergency is declared ... so extreme poverty is a state of emergency.’ When Edric was not conducting operations, he would assist his colleague Margaret Neave in the children’s department or help Jack to run an outpatient clinic. Patients would come from afar. There was always someone desperate to be seen. At the end of his long days, Edric would go back to the house he shared with other team members and flop, exhausted, onto his bed, oblivious to the clunking electric fan. But on a deep level, he was energised. On 20 May he wrote home, ‘Do you ever have that feeling that you’re doing what you’ve always wanted to do? Well, that’s how I feel now, but the work is often horribly frustrating and one feels so dreadfully ignorant.’ About Kate Day Kate Day is a researcher and advocate living in Wellington. She works on a variety of social and environmental issues and supports the church to speak up on such issues. Earlier in her career she spent time living in China and Cambodia and there she developed a longstanding fascination with Asia. She is married to John-Luke and they have two children. Call Me Brother is her first book. Call Me Brother: The Story of a New Zealand Doctor in Bangladesh is available in paperback and e-book at www.kailakuri.com/biography, with all proceeds going to the Kailakuri Healthcare Project. Watch Kate Day explain the book in this three-minute video.

2 Comments

Between Maungakiekie and the Manukau: An Onehunga Childhood 1939-1948 by Jeanette de Heer One of my favourite Auckland walks takes me right around Maungakiekie/One Tree Hill. When I reach the slopes on the southern side I always stop and look down to Onehunga. From the edge of the parkland, houses spread down the hill to the industrial area where the land flattens out and meets the shores of the Manukau Harbour where there’s a wharf. It was near the wharf in a small nursing home known as Nurse Whitehead’s where I was born on the twentieth of September 1939 and it was between Maungakiekie and the Manukau that I lived for the first nine years of my life. This is how author Jeanette de Heer opens her memoir of childhood, a collection of vividly recalled and precisely delineated memories of her early years in Onehunga up until 1948 when the family moved to a new home in the Auckand suburb of Oranga. Between Maungakiekie and the Manukau: An Onehunga Childhood 1939-1948 is a short book, just 63 pages in length, beautifully produced by Mary Egan Publishing, that reads as a series of pungent vignettes written by an author who has the gift of being able to re-enter her early memories and communicate directly the perspective of the small child. This book had its beginnings in a short piece, 'My world as a child' written in 2002 in response to reading Margaret Atwood's famous book on writing Negotiating with the Dead: A Writer on Writing (2002). Jeanette then 'put the piece aside and didn't think about it again' until she enrolled on a 2011 summer school of life writing at the Centre for Lifelong Learning at the University of Auckland. On that course Jeanette began work on a series of short pieces about her birth and childhood, including an account of her first home and its environs that would later provide the framework and some of the content of her book. In these stories Jeanette was evoking a time, long past, where people lived in close knit communities and where the rhythms of daily life were simpler, gentler, warmer and highlights were; the arrival of letters and presents from a grandmother in England; dances at the local RSA where the children got to skate in their socks over the powdered floor; the novelty of the chewing gum, that came in strips wrapped in foil, gifts from the North American soldiers stationed in Auckland during the war years; or a day long family outing involving, tram, ferry and bus to visit favourite relatives in Birkenhead. Her account of starting school and the strangeness of the new routines and the different teaching styles are written with freshness and humour. And that is the charm of this book, the way it offers a candid and engaging historical account of how life was lived in New Zealand in the 1940s, as seen through the eyes of an inquisitive little girl. For people interested in recording their life story primarily for family and friends, Jeanette’s book, the writing of it and the production process illustrates just how possible it is to write and publish a memoir. Jeanette chose to explore a short well-defined period in her life, a time she remembered fondly. With a small and realistic goal like this and a straightforward method — she used the short, rapid writing technique taught in my classes to discover her material — she remained on task and was able to bring her project to fruition. She then built her book, story by story until she had a satisfactory first draft ready for editing. Following the edit she then employed Mary Egan, New Zealand’s premium self-publisher, and her team, daughters Sophie and Anna, to manage the production, including the copy edit, the design of the cover and page layout and the commercial printing of the manuscript. The production process took four months. Book extract ‘Exploring Onehunga’ Bob and I liked exploring beyond our own backyard. The ‘stinky fern paddock’ further down our street was a great place for a game of hide and seek though we hated the strong smell of the fennel that grew there. A more appetising smell came from Waldron’s confectionary factory. When they were making their butterscotch the smell was particularly enticing. Mr Dean, our milkman, kept his horse Horace in a nearby field and Bob and I liked to help feed him. I was both fascinated and repelled by his large yellow teeth munching on the oats. Would Horace bite? Onehunga Beach was only a short distance away and a good place for fossicking. At low tide we sometimes followed the shoreline round to Hillsborough. One summer I got my first bad case of bad sunburn while at the beach. Big blisters came up on my shoulders. Often on our roamings Bob and I came upon groups of old Maori women sitting in doorways. They were usually dressed in black with headscarves tied over their white hair and their flax ketes beside them. Some of the women had the moko tattooed on their chin. We once stood on the footpath and watched a tangi taking place at a nearby house. On the verandah we could see an open coffin draped in greenery surrounded by weeping women. A photograph of the deceased was displayed at the head of the coffin. Streams of mourners were entering and leaving the house. Neither Bob nor I had ever seen anything like this before. Bob says we went inside but I don’t remember that. Sometimes we would spy Old Jerry, a sad casualty of World War 1, limping around the streets muttering to himself. We’d whisper to each other, ‘He’s got a steel plate in his head.” We were curious about another neighbour, Mrs Tyne, and her collection of Manx cats. She lived alone in a dark house and all her cats had their tails cut off. When one of the local boys hit a cricket ball through Mrs Tyne’s front window no one was brave enough to own up to the deed and retrieve the ball. Sometimes we encountered a strongly built Maori boy, Todd Wade. He delighted in frightening us by saying, “I’ll put in a big pot and cook you!” That sent us scampering away and made Todd laugh... Jeanette de Heer, Between Maungakiekie and the Manukau: An Onehunga Childhood 1939-1948, Auckland: Conehaven Books, 2016:45-46 About Jeanette de Heer Jeanette de Heer was born in Onehunga in 1939. She trained as a primary school teacher and taught in Auckland and London. In 1985 Jeanette enrolled in studies at Auckland University and graduated with a BA and an MA (Hons) in Sociology. Attending Deborah Shepard’s five day Life Writing workshop in 2011 she says was 'a pleasure from beginning to end. The opportunity to work under Deborah's gentle and encouraging guidance in a well structured series of free writing exercises, reading my stories aloud to the group and hearing group members’ stories made me realise that I could write a memoir of my early childhood that I could self-publish." Jeanette still belongs to the life writing group that formed after Deborah’s course. Jeanette is a mother and a grandmother and when she is not writing enjoys reading, walking, films, the theatre, orchestral concerts and spending time with her family and friends. |

AuthorsArchives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed