|

Update

Recently Deborah conducted a mentoring session with a friend from way back, someone from boarding school years, whom she hadn’t seen in a very long time but who shares a love of writing. They met in a very beautiful setting, at the new library in the village of Waitati, twenty minutes north of Dunedin. Together they wrote down their writing goals and then in fifteen minutes wrote a short piece on the theme, selected by her friend, ‘The rivers of my life.’ This is what they wrote in a rush, what came tumbling out with the timer ticking. |

The rivers of my life by Nicola Holmes

|

My first river memory is of a stream. Bowyers stream, which I visited often as a child. The place was special and visits were always eagerly anticipated.

The warm stones of the riverbed under my feet. This was summer, the 1960s, Canterbury. Scorching hot days, ripening crops and anticipation of frolicking in a warm stream. Always warmer on top than below, a little deeper. There was the familiar smell of a little of nature’s silt in the air, a bit muddy and yet fresh at the same time. Willows were there for shade and for us to jump and dive off. The fibrous roots deep down in the river banks – red and strong. The green of the leaves too is a strong memory along with their ability to dance in the breezes. |

|

We went in the afternoons as a family to Bowyers stream. Dad was at home on the farm. Often we’d gather with relations and friends and the kids would play and our Mums would talk. Afternoon teas always came too – orange cordial in a flagon, tomato sandwiches, homemade biscuits (sometimes yoyos) and flasks for tea in a wicker basket.

There was no feeling of time – just the freedom to duck and dive and float in the gentle current, with or without a rubber inner tube. And to do noisy honey pots off the bank or the willow branch. |

We felt safe and nestled in the spot. The shingle bank, opposite the willows, heated by the sun was where we lay to warm away goose bumps. I felt really alive being in and out of the stream; wet to dry, wet to dry.

Simplicity was the essence of this place and our being in it. No complications – just child glee and fun; being there.

Sunlight glistened on these waters. I loved duck diving down to pick out coloured stones. I loved the shafts of sunlight filtering through the water from above. And chasing the darting tadpoles. It was a victory if some made it into the jar.

Calling into the Alford Forest store, on the way home, for an ice cream slice was the best treat after being tired out and a little bit sunburnt from the afternoon frolics. There was a real art to licking the melting ice cream from around the edges of the pink wafers and to keep it from squishing onto my lap.

The big river in my life and the essence of my mihi is the Rakaia, flowing as it does from the majestic Southern Alps to the sea.

The Rakaia is powerful, braided and splays down the plains. It’s a huge life force which supports so much of nature. In flood it is truly awesome; raging through the gorge telling us humans who is in charge.

This river links me to my place in the world. Even living amidst cities, as I have, its essence provides strength. The rounded boulders, tumbled over and over hold many more deep secrets than their geology displays.

It tells me again, this river, that each of us are mere mortals on our spinning planet Gaia. And lest we forget; her sanctity, her life sustaining energy.

I have long been yearning to write and taking the first step has been made easier by working with Deborah. I grew up in rural Mid Canterbury and returned to live rurally again in my mid forties. I’m deeply linked in with nature and derive delight from observing its gifts, changing hourly as they do. Nicola.

Simplicity was the essence of this place and our being in it. No complications – just child glee and fun; being there.

Sunlight glistened on these waters. I loved duck diving down to pick out coloured stones. I loved the shafts of sunlight filtering through the water from above. And chasing the darting tadpoles. It was a victory if some made it into the jar.

Calling into the Alford Forest store, on the way home, for an ice cream slice was the best treat after being tired out and a little bit sunburnt from the afternoon frolics. There was a real art to licking the melting ice cream from around the edges of the pink wafers and to keep it from squishing onto my lap.

The big river in my life and the essence of my mihi is the Rakaia, flowing as it does from the majestic Southern Alps to the sea.

The Rakaia is powerful, braided and splays down the plains. It’s a huge life force which supports so much of nature. In flood it is truly awesome; raging through the gorge telling us humans who is in charge.

This river links me to my place in the world. Even living amidst cities, as I have, its essence provides strength. The rounded boulders, tumbled over and over hold many more deep secrets than their geology displays.

It tells me again, this river, that each of us are mere mortals on our spinning planet Gaia. And lest we forget; her sanctity, her life sustaining energy.

I have long been yearning to write and taking the first step has been made easier by working with Deborah. I grew up in rural Mid Canterbury and returned to live rurally again in my mid forties. I’m deeply linked in with nature and derive delight from observing its gifts, changing hourly as they do. Nicola.

The rivers of my life by Deborah Shepard

|

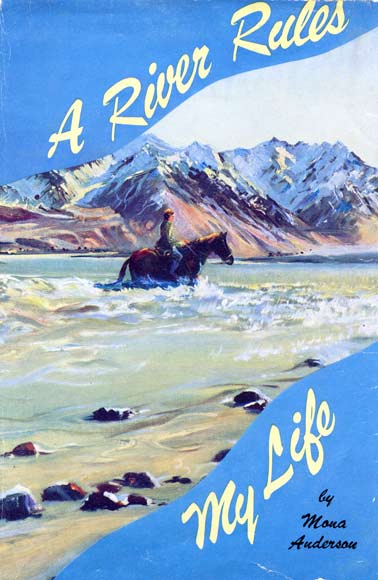

Rivers of my life reminds me of the title of the very first memoir I read as an adolescent growing up on a farm in Ellesmere. It was an account of life on a high-country sheep station on Mt Algidus in Canterbury and it was by Mona Anderson. Her book, A River Rules My Life (1963) caught at my imagination because it was real and relevant and described the rhythms of daily life in an extraordinary setting in mountains I knew, the Southern Alps. She wrote about bright, clear sunshine days where the sun dazzled on shining, melting snow on Mt Algidus. She described storms and swollen rivers, in flood, that took with them sheep and horses, knocking them over and rushing them downstream to wash up, eventually, on a shingle bank, in a curve of the river along with smooth, grey tree trunks, dead. Mona Anderson could see the river from her kitchen window and it modulated her days and determined her life, whether the supplies got through or didn’t, whether husbands and farm workers and shepherds got back for dinner, or in the dark, or days later...

|

The first river in my life was the Avon River in Christchurch, a river we thought of then as English because it wound through a town of Gothic red brick and grey stone buildings straight out of the architectural pattern books of England and Europe. It isn’t like that anymore. The buildings have gone and the earthquakes have thrown the river into the air 20 centimetres twisting and wrenching its sinuous curves into new less appealing shapes while liquefaction has forced the mud of the swamps up, and changed the riverbeds.

When Maori first discovered Canterbury they didn’t try to dwell on the swamp where all the rivers and its tributaries ran, although they did treat it as a food basket. Their largest settlement was at Kaiapoi and another was at Rapaki between Lyttelton and Governor’s Bay and yet another further south at Taumutu on the edge of Lake Ellesmere. Today the forest green and ochre riverweed is sparse and there seem to be fewer eels and trout. I saw just one eel and one big bronze duck, last week, when I stood on a bridge in the Botanic Gardens, looking down scanning the bottom for signs of life.

The next river I remember was the Selwyn River in Ellesmere, shallow in places, deeper there and forming a ‘swimming hole’, rushing over dark greywacke pebbles, through flowering watercress and buttercup and a mauve wildflower, I can’t name, and under bending willows their elegant fine branches and tiny bright lime leaves like cut up pieces of paper dipping right into the water.

I remember tyre swings above the water and swinging out higher and wider and the boys leaping off and flying through the air doing honeypots. Sometimes they grabbed at dozens of long, thin strands of willow, pulling them together to launch out and jump in. I remember a whole afternoon at Coes Ford riding a blow-up lilo, down the river, laughing at the hectic motion and then getting off in the shallows and dragging the lilo back up the riverbed and starting all over again. Tim, was there riding the lilo, and Kate and Matthew, and Penny and Tom and Kit.

On tartan rugs in the shade under the willows our mothers sat; Mum, Betty and Moira surrounded by the picnic baskets, the thermoses of tea, the milk and sugar in green Bakerlite containers and the afternoon tea – tomato sandwiches made with white bread and butter and a sprinkle of salt and a pinch of sugar, chocolate chippie biscuits with the fork mark in the dough and Louise Slice with a nutmeg flavoured base and jam sandwiched in the middle and jelly crystals on the icing, always sweet and too much and very yummy.

Mum and Moira were breastfeeding a baby each. Mum was happy there with her friends in the dappled willow leaf light. I see her wearing a sun frock, she had made out of olive-green linen that matched her hazel eyes. It had wide straps and a matching linen belt. On her wrist at that time – the 1970s – she wore an enamel bracelet in shades of bright and dark green, big rectangles of dripped colour, the pieces joined together with copper wire.

It would have been baby Jen, my little sister, twelve years younger, at my mother’s breast, sucking studiously, working her jaws, gulping and making the little hiss-sigh that comes after, while a small hand with tiny, surprisingly sharp nails clutched at her breast leaving miniature scratches on the pearly white skin amongst the tracery of purple veins. The sounds would be children’s voices, water running over stones, the whirring sound of bees over white and purple clovers. A buzz. The brilliant grass blades under the willows were long and soft…

Postscript

Yesterday in Christchurch I read this story to my mother, out on the sunny front porch at the rest home in Merivale where she lives, checking on the accuracy of my details. Mum couldn’t remember the olive-green linen dress but she remembered another one,

‘It was off-white with irregular lines of a lighter spring green and a darker green.’

‘No Mum, that’s not the one. It was definitely olive green and it was linen.’ I felt so sure of this.

‘You’re not thinking of the deep green silk dress I made to wear at your wedding?’

‘No,’ I said firmly but beginning to feel uncertain.

‘I will have to think about it,’ she said. ‘You might be right. The enamel bracelet was a present from the artist mother of a little boy I taught at Elmwood School.’

The boy you saved from drowning?

No that was another child. Remember how I dived into the pool in my dress and shoes and forgot to take my watch off.

I did remember that and the rest of the story where she walked back past the classrooms with her dripping dress clinging to her body, showing the red knickers she was wearing that day.

‘Have I got greywacke right?’ I asked. By now my husband was involved and using his Iphone to check on Google. On the ecan (Environment Canterbury Regional Council) website he found references to the greywacke Selwyn riverbed and yards of other geomorphological information. ‘Yes greywacke,’ he said.

When Maori first discovered Canterbury they didn’t try to dwell on the swamp where all the rivers and its tributaries ran, although they did treat it as a food basket. Their largest settlement was at Kaiapoi and another was at Rapaki between Lyttelton and Governor’s Bay and yet another further south at Taumutu on the edge of Lake Ellesmere. Today the forest green and ochre riverweed is sparse and there seem to be fewer eels and trout. I saw just one eel and one big bronze duck, last week, when I stood on a bridge in the Botanic Gardens, looking down scanning the bottom for signs of life.

The next river I remember was the Selwyn River in Ellesmere, shallow in places, deeper there and forming a ‘swimming hole’, rushing over dark greywacke pebbles, through flowering watercress and buttercup and a mauve wildflower, I can’t name, and under bending willows their elegant fine branches and tiny bright lime leaves like cut up pieces of paper dipping right into the water.

I remember tyre swings above the water and swinging out higher and wider and the boys leaping off and flying through the air doing honeypots. Sometimes they grabbed at dozens of long, thin strands of willow, pulling them together to launch out and jump in. I remember a whole afternoon at Coes Ford riding a blow-up lilo, down the river, laughing at the hectic motion and then getting off in the shallows and dragging the lilo back up the riverbed and starting all over again. Tim, was there riding the lilo, and Kate and Matthew, and Penny and Tom and Kit.

On tartan rugs in the shade under the willows our mothers sat; Mum, Betty and Moira surrounded by the picnic baskets, the thermoses of tea, the milk and sugar in green Bakerlite containers and the afternoon tea – tomato sandwiches made with white bread and butter and a sprinkle of salt and a pinch of sugar, chocolate chippie biscuits with the fork mark in the dough and Louise Slice with a nutmeg flavoured base and jam sandwiched in the middle and jelly crystals on the icing, always sweet and too much and very yummy.

Mum and Moira were breastfeeding a baby each. Mum was happy there with her friends in the dappled willow leaf light. I see her wearing a sun frock, she had made out of olive-green linen that matched her hazel eyes. It had wide straps and a matching linen belt. On her wrist at that time – the 1970s – she wore an enamel bracelet in shades of bright and dark green, big rectangles of dripped colour, the pieces joined together with copper wire.

It would have been baby Jen, my little sister, twelve years younger, at my mother’s breast, sucking studiously, working her jaws, gulping and making the little hiss-sigh that comes after, while a small hand with tiny, surprisingly sharp nails clutched at her breast leaving miniature scratches on the pearly white skin amongst the tracery of purple veins. The sounds would be children’s voices, water running over stones, the whirring sound of bees over white and purple clovers. A buzz. The brilliant grass blades under the willows were long and soft…

Postscript

Yesterday in Christchurch I read this story to my mother, out on the sunny front porch at the rest home in Merivale where she lives, checking on the accuracy of my details. Mum couldn’t remember the olive-green linen dress but she remembered another one,

‘It was off-white with irregular lines of a lighter spring green and a darker green.’

‘No Mum, that’s not the one. It was definitely olive green and it was linen.’ I felt so sure of this.

‘You’re not thinking of the deep green silk dress I made to wear at your wedding?’

‘No,’ I said firmly but beginning to feel uncertain.

‘I will have to think about it,’ she said. ‘You might be right. The enamel bracelet was a present from the artist mother of a little boy I taught at Elmwood School.’

The boy you saved from drowning?

No that was another child. Remember how I dived into the pool in my dress and shoes and forgot to take my watch off.

I did remember that and the rest of the story where she walked back past the classrooms with her dripping dress clinging to her body, showing the red knickers she was wearing that day.

‘Have I got greywacke right?’ I asked. By now my husband was involved and using his Iphone to check on Google. On the ecan (Environment Canterbury Regional Council) website he found references to the greywacke Selwyn riverbed and yards of other geomorphological information. ‘Yes greywacke,’ he said.

|

In the meantime I had been searching, unfruitfully, for the book A River Rules My Life in Auckland and online. I wanted to read it again to see whether it gave me the same thrill. So following the visit to my mother we went to the new Victorian-influenced shopping arcade that was once Wilson’s Tannery at Woolston and found there Smith’s bookshop that used to be on Manchester Street - a very old, charming shop with shelves to the roof, groaning with books, and more on the mezzanine, like a bookstore in Dickens England, but sadly swept away now by the bulldozer. I entered the shop in hope.

‘Ah,’ said the owner Barry Hancox, ‘I have one copy,’ and he walked straight to the shelf, reached with his index finger and plucked out a book with a beautiful cornflower blue cover, with a flourish and a smile. And there it was, The River Rules My Life with a watercolour of the Wilberforce river on the cover, the water cream and pale blue with brush strokes of white sparkle rippling over brown and red flecked boulders. And there, in the centre is a woman, sitting upright, Mona Anderson, riding her chestnut horse through the rush of water. |