Merimeri Penfold 26 May 1920 - 1 April 2014

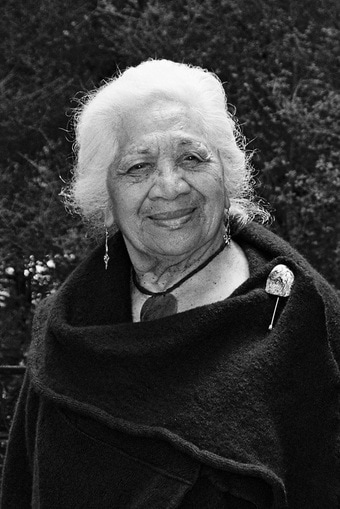

Merimeri Penfold, 2008 by Martin Friedlander

Merimeri Penfold, 2008 by Martin Friedlander

Dr Merimeri Penfold, Ngati Kuri, born in 1920 in Te Hãpua, an isolated Mãori community in the far north of New Zealand, near Cape Reinga, has died. Merimeri Penfold, Whãea of the University of Auckland, very first university teacher of the Mãori language in New Zealand from 1964, dominion vice president and inaugural member of the Mãori Women’s Welfare League, one of New Zealand's finest translators and a contributor to the seventh edition of the definitive Williams dictionary of Mãori language, translator of nine Shakespearean love sonnets, Ngã Waiata Aroha Love Sonnets (2000), co-editor of The Book of New Zealand Women: Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa (1993), co-author of Women in the Arts in New Zealand (1986) first woman to write a haka and perform it in protest over the All Black tour of South Africa in 1976, campaigner for a marae on the University of Auckland campus for which she received an honorary doctorate in 2000, a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her services to Maori in 2001, Human Rights Commissioner 2002 - 2007, a loved mother, grandmother, sister and friend has passed on. New Zealand has lost a wahine toa.

The following thoughts were recorded in my journal over three days as I responded first to the news of Merimeri’s death and then travelled to Northland for the third and final day of the tangi held at three venues; the Waiora Marae at Ngataki, the Te Reo Mihi Marae at Te Hãpua beside the Pãrengarenga Harbour and the burial ground at the Mareitu urupa on the hill overlooking the harbour.

The following thoughts were recorded in my journal over three days as I responded first to the news of Merimeri’s death and then travelled to Northland for the third and final day of the tangi held at three venues; the Waiora Marae at Ngataki, the Te Reo Mihi Marae at Te Hãpua beside the Pãrengarenga Harbour and the burial ground at the Mareitu urupa on the hill overlooking the harbour.

2 April 2014

I received a call from Lee Cooper at the University of Auckland, this morning telling me of Merimeri’s death. He was a colleague and friend of Merimeri’s. I heard the catch in his voice and felt the wave of sadness pass over. Always it is difficult to tell another person that someone special, someone who touched your life has passed on. ‘Did she die peacefully?’ I ask. ‘Yes,’ he said, 'she did.' I am teaching a Masterclass in memoir at the Michael King Writers’ Centre this evening. I will take a bunch of deep magenta roses from my garden to remember Merimeri. At the beginning of the session I will light a candle and set it beside the roses and the book Her Life’s Work that features the black and white photograph of Merimeri by photographer Marti Friedlander, alongside the four other bold, original, creative women who featured in that work; her friend the anthropologist Anne Salmond, the painter Jacqueline Fahey, the film maker Gaylene Preston and writer Margaret Mahy. I will open the session by paying tribute to Merimeri.

I received a call from Lee Cooper at the University of Auckland, this morning telling me of Merimeri’s death. He was a colleague and friend of Merimeri’s. I heard the catch in his voice and felt the wave of sadness pass over. Always it is difficult to tell another person that someone special, someone who touched your life has passed on. ‘Did she die peacefully?’ I ask. ‘Yes,’ he said, 'she did.' I am teaching a Masterclass in memoir at the Michael King Writers’ Centre this evening. I will take a bunch of deep magenta roses from my garden to remember Merimeri. At the beginning of the session I will light a candle and set it beside the roses and the book Her Life’s Work that features the black and white photograph of Merimeri by photographer Marti Friedlander, alongside the four other bold, original, creative women who featured in that work; her friend the anthropologist Anne Salmond, the painter Jacqueline Fahey, the film maker Gaylene Preston and writer Margaret Mahy. I will open the session by paying tribute to Merimeri.

Later

On the volcanic cone of Takarunga, outside the Michael King Writers’ Centre writing alongside the memoirists, an exercise in writing quickly, on the pulse, naming thoughts and feelings as I respond to the scene in front of me. I hear the birds; the dove coo, the tui wardle, the sparrow cheep. Inside a candle is burning for a woman of grace and generosity, a woman of mana and dignity, a woman of wisdom. Merimeri Penfold, a great Mãori kuia has died. I can see, way in the distance the earth red buildings and rooftops of the Õrãkei marae at Takaparawha, Bastion Point. Merimeri and her friend Anne Salmond campaigned for over a decade to have a marae built on the University of Auckland campus. There, as a lecturer of the Mãori language, Merimeri brought tikanga Mãori into the academy. The wind murmurs. The glass blades long and lush, they shiver. The birds sing again. Merimeri is gone, my life has it challenges, but here in this moment I will breathe with the luxuriant soft grasses and acknowledge her passing. Many of the writers knew Merimeri. Some were her students. The sadness again. A seagull cries from far away. Merimeri has died at the grand age of ninety-three, a terrific age, a life well lived they would say, and yet still it is a loss, reminding me of the ephemeral nature of existence. It is difficult at times like this not to view the road ahead as strewn with more losses; loss of health, vitality, loved ones, life. But Merimeri lived and she made a difference. There are three, four seagull voices chanting together now.

On the volcanic cone of Takarunga, outside the Michael King Writers’ Centre writing alongside the memoirists, an exercise in writing quickly, on the pulse, naming thoughts and feelings as I respond to the scene in front of me. I hear the birds; the dove coo, the tui wardle, the sparrow cheep. Inside a candle is burning for a woman of grace and generosity, a woman of mana and dignity, a woman of wisdom. Merimeri Penfold, a great Mãori kuia has died. I can see, way in the distance the earth red buildings and rooftops of the Õrãkei marae at Takaparawha, Bastion Point. Merimeri and her friend Anne Salmond campaigned for over a decade to have a marae built on the University of Auckland campus. There, as a lecturer of the Mãori language, Merimeri brought tikanga Mãori into the academy. The wind murmurs. The glass blades long and lush, they shiver. The birds sing again. Merimeri is gone, my life has it challenges, but here in this moment I will breathe with the luxuriant soft grasses and acknowledge her passing. Many of the writers knew Merimeri. Some were her students. The sadness again. A seagull cries from far away. Merimeri has died at the grand age of ninety-three, a terrific age, a life well lived they would say, and yet still it is a loss, reminding me of the ephemeral nature of existence. It is difficult at times like this not to view the road ahead as strewn with more losses; loss of health, vitality, loved ones, life. But Merimeri lived and she made a difference. There are three, four seagull voices chanting together now.

4 April 2014

We are on a tiny plane, my sister and I, travelling north to Kerikeri to Merimeri’s tangi. The plane, making a lot of noise, huffing and puffing, is pushing forward and I have an image suddenly of Jean Batten in her Gypsy Moth on the last leg of her journey flying across the Pacific, all the way from England to New Zealand on her solo voyage to break a record. Another courageous woman. The sea is deep teal brushed with a granite sheen giving it the texture of pottery. Waves shaped like white eyelashes appear suspended in motion. I have never flown up the tip of the North Island before, never seen the land from this vantage point and so had not realised how many islands hug the coastline and that just below Wellsford, the land narrows into a neck with the Kaipara Harbour on one side and the Pacific Ocean on the other. There are clouds all the way along Aotearoa, the Land of the Long White Cloud, and they are broken up into balls of wool, and puffs of steam, some are icebergs, some soft icing shapes. Down below a silver river snakes and coils through a landscape of green native bush.

As the plane flies from the city of Auckland towards Northland, the place of Merimeri’s childhood, I reflect on the journey she made as a girl of thirteen to boarding school in a cold, harsh city far away from her family in Te Hapua and the good life she had known living off the land and the sea. She referred to the Pãrengarenga harbour as the community food basket. ‘We lived on fish. There was an endless variety of seafood – mullet, snapper, maomao, kahawai, trevally, shark, scallops, cockles, octopus, crab and periwinkle. The fish was smoked and preserved. We only ever took what was needed.’

It was at primary school that Merimeri’s teacher Miss Jean Archibald noticed two bright, little buttons in her class, Merimeri and her friend Mira Szászy, and negotiated with their parents to send them to Queen Victoria School for Mãori Girls in Auckland. Merimeri said when she first saw Miss Archibald she was fascinated. ‘She had tiny feet, and tiny, tiny fingers but those tiny feet were ever so elegant. I used to look at her and think I would like to be a teacher like her. That was how she impressed me.’ But still Merimeri wondered how Miss Archibald managed to persuade her parents to part with their eldest daughter and send her south for an education. This was a turning point. It would be her route to a career in education spanning five decades but initially she found the transition difficult and traumatising. Her mother died while Merimeri was away. She died giving birth to her eighteenth child - along with the baby - and Merimeri was unable to attend the tangi because of an outbreak of polio in Northland. There was a ban on travel to the area. She said, ‘I was devastated. I went to my dormitory and climbed into bed feeling truly desolate. My mother deserved better.’ The loss of her mother and the death of Merimeri’s firstborn, a full term baby son were the lowest and hardest moments in her life. When I asked her what had sustained her through the losses she said it was thinking of her mother and her quiet strength, ‘She was just a girl when my father met her, a tiny young girl and very quiet playing the role of mother. She had to be tough. When she was pregnant she still had to dig gum and those sorts of things, and she somehow kept up a sense of purpose and responsibility and ran that home so well. That for me is what she left with us, that strength of purpose and the appreciation of having a tidy, well-ordered home.’

The land now is jade green with seams of lighter and darker green, like the striation in a pounamu pendant. The plane is flying low as we approach the airstrip at Kerikeri over bright green hills that have been pinched and ruched into folds. I see a hedge in the shape of a large cross, like a jeweller’s pin, and poplars, with foliage like ochre feathers, poked into the ground. There are houses and barns, dirt tracks and shelterbelts, the curling line of a shining river and willows, a wash of lime green, tracing the winding tributary. Again and again I feel lucky to live in this land. The plane engine is making a screaming sound like a squawking seagull skidding in to land. It runs down the runway, past a line of toi toi, the foliage like cream hair blowing in the wind.

I have never been to a tangihanga before and am curious and nervous. Will I know what to do? When I first approached Merimeri about recording her story for Her Life’s Work I wondered whether I was the right person to undertake the collaboration. I was aware of the academic debates around the inappropriateness of Pãkehã attempting to represent the stories of Mãori. I had encountered them personally when I wrote my history of New Zealand women in film and I did not want to offend but Merimeri was a teacher and saw in my project the potential to educate people, by telling her story. She would educate me, and my reader, in the ways of her people. And so during the three years that we conversed and worked together on the manuscript she raised my awareness, gently, through storytelling and instruction making me keen to understand more and giving me the confidence to make my own personal journey of exploration. In 2008 I attended a põwhiri at the Õrãkei marae at Bastion Point to mark thirty years on from day 507, the final day of a peaceful protest, led by Joe Hawke, over the government’s planned confiscation of Mãori land for a housing subdivision for the wealthy. Also in that year I attended an open day and powhiri, with my mother, at the Taumutu marae, the meeting place of Ngati Moki on the edge of Waihora, Lake Ellesmere in Canterbury near where I grew up. It was on that trip that my mother told me about the very first powhiri I attended at Te Awhitu House, the former home of Horei Kerei Taiaroa, the first member of parliament for Southern Maori, elected in 1871. 'You were three years old,' said my mother. At that ceremony our family was returning a patiti to the Taiaroa family. The MP had given this treasured object to my great-grandfather Joseph Doyle, as a token of friendship and thanks for looking after his farm when the MP was away on parliamentary business in Wellington. My mother told me it was her first experience of a powhiri and it moved her deeply. 'I was by struck by the richness of Maori culture, of its meaningful traditions and sacred rituals. Our own culture seemed arid in contrast.'

For the launch of Her Life’s Work in 2009 Merimeri organised a põwhiri. She did it quietly, tugging gently on a few strings; that was how she worked, deftly and gracefully. She was a mover and a shaker and a bridge between the cultures. I remember the kaumātua, representing the Waipapa university marae, welcoming Merimeri and Anne Salmond and the guests. The book was placed on a korowai, a feather cloak, and out of the swell of his deep-toned lyrical language I heard the title, Her Life’s Work and knew he was blessing it and felt it to be a deep honour. It is in these bi-cultural moments where Mãori dignify a meaningful event with sacred ceremonial ritual that I think we are blessed to be living in Aotearoa. Tikanga Mãori is at the throbbing heart of Mãori culture. The rituals say “This is important, this is precious, mark this, dignify it, remember it.’

I wonder what will happen over the next two days. I tell myself to watch. Listen. Learn. Breathe.

Later in the day

We are staying overnight in a little house by the sea at Ahipara, at the beginning of the Ninety Mile Beach. We got here in the dark, after making numerous false turns and ending up at a deserted house. As the car lights swept across the grass illuminating tropical palms and a lived in, but empty house, we felt confused. Where were we? The air was warm and sultry, cicadas were still chirruping and we could hear the sea pushing onto the beach. I phoned Nola, the owner of the bed and breakfast, and discovered that she was just next-door.

We are on a tiny plane, my sister and I, travelling north to Kerikeri to Merimeri’s tangi. The plane, making a lot of noise, huffing and puffing, is pushing forward and I have an image suddenly of Jean Batten in her Gypsy Moth on the last leg of her journey flying across the Pacific, all the way from England to New Zealand on her solo voyage to break a record. Another courageous woman. The sea is deep teal brushed with a granite sheen giving it the texture of pottery. Waves shaped like white eyelashes appear suspended in motion. I have never flown up the tip of the North Island before, never seen the land from this vantage point and so had not realised how many islands hug the coastline and that just below Wellsford, the land narrows into a neck with the Kaipara Harbour on one side and the Pacific Ocean on the other. There are clouds all the way along Aotearoa, the Land of the Long White Cloud, and they are broken up into balls of wool, and puffs of steam, some are icebergs, some soft icing shapes. Down below a silver river snakes and coils through a landscape of green native bush.

As the plane flies from the city of Auckland towards Northland, the place of Merimeri’s childhood, I reflect on the journey she made as a girl of thirteen to boarding school in a cold, harsh city far away from her family in Te Hapua and the good life she had known living off the land and the sea. She referred to the Pãrengarenga harbour as the community food basket. ‘We lived on fish. There was an endless variety of seafood – mullet, snapper, maomao, kahawai, trevally, shark, scallops, cockles, octopus, crab and periwinkle. The fish was smoked and preserved. We only ever took what was needed.’

It was at primary school that Merimeri’s teacher Miss Jean Archibald noticed two bright, little buttons in her class, Merimeri and her friend Mira Szászy, and negotiated with their parents to send them to Queen Victoria School for Mãori Girls in Auckland. Merimeri said when she first saw Miss Archibald she was fascinated. ‘She had tiny feet, and tiny, tiny fingers but those tiny feet were ever so elegant. I used to look at her and think I would like to be a teacher like her. That was how she impressed me.’ But still Merimeri wondered how Miss Archibald managed to persuade her parents to part with their eldest daughter and send her south for an education. This was a turning point. It would be her route to a career in education spanning five decades but initially she found the transition difficult and traumatising. Her mother died while Merimeri was away. She died giving birth to her eighteenth child - along with the baby - and Merimeri was unable to attend the tangi because of an outbreak of polio in Northland. There was a ban on travel to the area. She said, ‘I was devastated. I went to my dormitory and climbed into bed feeling truly desolate. My mother deserved better.’ The loss of her mother and the death of Merimeri’s firstborn, a full term baby son were the lowest and hardest moments in her life. When I asked her what had sustained her through the losses she said it was thinking of her mother and her quiet strength, ‘She was just a girl when my father met her, a tiny young girl and very quiet playing the role of mother. She had to be tough. When she was pregnant she still had to dig gum and those sorts of things, and she somehow kept up a sense of purpose and responsibility and ran that home so well. That for me is what she left with us, that strength of purpose and the appreciation of having a tidy, well-ordered home.’

The land now is jade green with seams of lighter and darker green, like the striation in a pounamu pendant. The plane is flying low as we approach the airstrip at Kerikeri over bright green hills that have been pinched and ruched into folds. I see a hedge in the shape of a large cross, like a jeweller’s pin, and poplars, with foliage like ochre feathers, poked into the ground. There are houses and barns, dirt tracks and shelterbelts, the curling line of a shining river and willows, a wash of lime green, tracing the winding tributary. Again and again I feel lucky to live in this land. The plane engine is making a screaming sound like a squawking seagull skidding in to land. It runs down the runway, past a line of toi toi, the foliage like cream hair blowing in the wind.

I have never been to a tangihanga before and am curious and nervous. Will I know what to do? When I first approached Merimeri about recording her story for Her Life’s Work I wondered whether I was the right person to undertake the collaboration. I was aware of the academic debates around the inappropriateness of Pãkehã attempting to represent the stories of Mãori. I had encountered them personally when I wrote my history of New Zealand women in film and I did not want to offend but Merimeri was a teacher and saw in my project the potential to educate people, by telling her story. She would educate me, and my reader, in the ways of her people. And so during the three years that we conversed and worked together on the manuscript she raised my awareness, gently, through storytelling and instruction making me keen to understand more and giving me the confidence to make my own personal journey of exploration. In 2008 I attended a põwhiri at the Õrãkei marae at Bastion Point to mark thirty years on from day 507, the final day of a peaceful protest, led by Joe Hawke, over the government’s planned confiscation of Mãori land for a housing subdivision for the wealthy. Also in that year I attended an open day and powhiri, with my mother, at the Taumutu marae, the meeting place of Ngati Moki on the edge of Waihora, Lake Ellesmere in Canterbury near where I grew up. It was on that trip that my mother told me about the very first powhiri I attended at Te Awhitu House, the former home of Horei Kerei Taiaroa, the first member of parliament for Southern Maori, elected in 1871. 'You were three years old,' said my mother. At that ceremony our family was returning a patiti to the Taiaroa family. The MP had given this treasured object to my great-grandfather Joseph Doyle, as a token of friendship and thanks for looking after his farm when the MP was away on parliamentary business in Wellington. My mother told me it was her first experience of a powhiri and it moved her deeply. 'I was by struck by the richness of Maori culture, of its meaningful traditions and sacred rituals. Our own culture seemed arid in contrast.'

For the launch of Her Life’s Work in 2009 Merimeri organised a põwhiri. She did it quietly, tugging gently on a few strings; that was how she worked, deftly and gracefully. She was a mover and a shaker and a bridge between the cultures. I remember the kaumātua, representing the Waipapa university marae, welcoming Merimeri and Anne Salmond and the guests. The book was placed on a korowai, a feather cloak, and out of the swell of his deep-toned lyrical language I heard the title, Her Life’s Work and knew he was blessing it and felt it to be a deep honour. It is in these bi-cultural moments where Mãori dignify a meaningful event with sacred ceremonial ritual that I think we are blessed to be living in Aotearoa. Tikanga Mãori is at the throbbing heart of Mãori culture. The rituals say “This is important, this is precious, mark this, dignify it, remember it.’

I wonder what will happen over the next two days. I tell myself to watch. Listen. Learn. Breathe.

Later in the day

We are staying overnight in a little house by the sea at Ahipara, at the beginning of the Ninety Mile Beach. We got here in the dark, after making numerous false turns and ending up at a deserted house. As the car lights swept across the grass illuminating tropical palms and a lived in, but empty house, we felt confused. Where were we? The air was warm and sultry, cicadas were still chirruping and we could hear the sea pushing onto the beach. I phoned Nola, the owner of the bed and breakfast, and discovered that she was just next-door.

It is good to be here after a long drive up from Kerikeri in the late afternoon light with a stop at Mangonui for fish and chips at a restaurant that sits on big piles over the water. At a high bench by an open window we goggled at the view across a tidal estuary. The water dusky pink and like a pearl was so still the surface had a curved lip on it. Seagulls flew over and some flapped right up close to the open window, trying to steal a chip from our plates.

Now I have my window open and can hear the ocean washing in and out, over and under, back and forth, big rolls of surf. The moon, in a sickle shape and golden orange floats with stars like white jasmine in an indigo sky. It is beautiful here. I understand why Merimeri, in the latter years of her life, wanted to return home to Te Hiku-o-te-Ika, the tail of the fish, one of the Mãori names for Northland. She was planning the move and talking about it when I recorded her story. She would live in a simple house with very little furniture, a couple of church pews for elders to sit on and perhaps some bean bags. She wanted mats woven from harakeke upon the floor. Above all her final home must be a functional space where people could gather to weave and talk, to fish in the stream nearby and to sleep at night.

I’m ready to fall into bed, now. The sheets on the bed are so clean. I can tell they have been dried outside because they smell of sunshine and sea. I feel safe here in nature’s embrace. Sweet dreams now. Tomorrow will bring an historic day.

I’m ready to fall into bed, now. The sheets on the bed are so clean. I can tell they have been dried outside because they smell of sunshine and sea. I feel safe here in nature’s embrace. Sweet dreams now. Tomorrow will bring an historic day.

5 April, very early morning, at Ahipara, at the bottom of the Ninety Mile Beach, preparing to leave for Ngataki. The trees here are bent sideways by the wind and the clouds greet us, flapping like pink flamingos their long necks outstretched in flight. I am standing on a path by the tussock looking at a stretch of water lined with bulrushes, the raupo. Nola called it a moat. How quickly the day dawns, the sky lightening from grey-blue with flushes of pink through to a pale blue-white like organza. My sister, who is into her second year learning te reo, told me just now that there are many different Mãori words to describe this time of day and the different mists that hug the land. I am transfixed by the sheer miracle of daybreak and by the waves surfing onto the shoreline, lines of froth and foam shooting joyfully along the beach as far as the eye can see.

10pm

We made it back to Kerikeri just an hour ago. This day has been so long and full, twelve hours in all, driving, up and down Te Hiku-o-te-Ika from the Waiora marae at Ngataki to the Te Reo Mihi marae and the Mareitu urupa at Te Hãpua and returning to the Waiora marae where the day had begun for the hãkari, the feast, where we sat at long trestle tables sharing food together. Throughout the day, as guests we were privileged to experience Mãori manaakitanga, a most marvellous display of Maori hospitality. Just before the big drive back from Te Hapua to Ngataki, the mourners were given food, from the back of a utility vehicle, parked on the road outside the urupa; egg sandwiches and spring water with slices of lemon and from a box, we were offered yellow pears from someone's garden.

The tangi had begun three days earlier with the arrival of Merimeri’s body from Kaitaia to the Waiora marae at Ngataki. Over three days family, friends and colleagues had been gathering to remember and share the stories and to pay their respects. These are my impressions of the final day: The female minister spoke of aroha and how Merimeri had so much to give. She spoke warmly too of the mokopuna, about nurturing them and helping the children find their place to stand, their türangawaewae, the place where they feel especially empowered and connected. She urged the men, the kaumātua, to go into schools and say to the principal “I’m here to talk to the young people”. She urged them to 'Inspire the children and guide them.' At the end of this first service, smiling brightly she said, ‘Oh dear where did all those words come from. I think it was Merimeri speaking through me.’

When I asked Merimeri to talk about the meaning of home she said it is not the physical home that matters, it is the family and maintaining connection between members of the whãnau that matters. ‘…keep your family ties strong and get in their way if you have to. Whatever you do, stay close. I never know whether my family want me or not but my philosophy is to participate in family life.’ She went on to say that when her daughter’s child was unwell she stepped in to help.

‘I literally carried him on my back for the first three years of his life to relieve him and support his mother. They were seriously considering me as Dominion President of the Maori Women’s Welfare League. It was a great position. Later they asked, ‘Why did you disappear from the scene you could have been Dominion President?’ She told them her commitment was to the family and she never regretted the decision, ’When you do that sort of thing, it strengthens you. It strengthens you and it doesn’t run you down.’

Today I observed the children at the marae and the urupa; little boys with tee shirts illustrated with cartoon characters, Rey Mystique and Nirvana, standing quietly in the sun holding flowers in a kete - no scuffling, no noise, no fidgeting. I have never seen such well-behaved children in all my life. They know the etiquette. I noticed too older sisters, fathers and grandfathers with toddlers in their arms. Some of the little ones were asleep, their limbs relaxed and floppy - cherished children. It hurt Merimeri to view the negative constructions of Mãori and their relationship to children on the six o’clock news. She was offended by the film Once Were Warriors and its bleak focus on the disturbed, dysfunctional aspects of the lives of gang families, people who are cut off from their roots, lives wrecked by alcohol and drugs. Child abuse happens in Pãkehã culture as well, but isn’t emphasized in the media in the same way. 'There was no hope in that film, it was destructive,' she said. 'The only positive that I remember was when they went into the marae and I saw the Mãori element that was healing. That girl looked at the marae and she felt safe there. It didn't say much and was only a small part of the film.'

When the formal speech making, the whaikorero, began and people stood and recounted the stories one of the themes was Merimeri’s gentle influence and how it rippled beyond her whãnau, to all the people she came in contact with through the workplace and the academy right out into the culture. There were people from the University of Auckland and the University of Victoria, from Mãori television and the Human Rights Commission and there were students and friends gathered there too. Merimeri was remembered in their speeches for making her mark through teaching the Mãori language and raising awareness of Te Ao Mãori across the campus. Her stamina and resilience were remarked upon too. For fifteen years she campaigned with Anne Salmond and Pat Hohepa for a marae on the university grounds. The Waipapa marae would function as a learning environment to teach marae protocol to students. It would be a place to formally welcome visitors to the university and it would attract Mãori students to academic study. When the marae project was achieved, Merimeri and fellow campaigners brought pressure to bear on the university to create a separate Mãori Studies department because until then Mãori studies had been taught within the department of Anthropology. In her eighties Merimeri was still bringing Mãori ritual into the graduation ceremonies at Auckland University by performing the karanga, in her beautiful voice, to welcome the students who were graduating. To hear her call would raise the hairs on your neck.

Being at a tangihanga a person receives an immersive experience in Maori culture. There were times when listening to the oratory and observing the graceful interpolation of speeches followed by waiata when it felt as though the present moment existed outside of time. I was conscious of the deep reach of history and the whaikorero linking back to ancient traditions established well before European contact. When Mãori sing waiata, the male and female voices meld into glorious harmonies and the music moves in waves, layer upon layer of rich, melodious sound swelling up to the rafters. I remember Merimeri talking about her experience teaching Mãori children in the 1940s in remote schools in the central North Island; Upper Minginui Forest Primary School in Tühoe country, Te Whaiti Primary School near Ruatahuna, the Rãtana Pã in Wanganui and Poroporo Primary School in Whakatãne. She believed you needed to build on their strengths and give them a positive experience and so she always addressed them in Mãori even though the language was banned from classrooms at that time. 'When you suppress the language, you suppress the culture because the two are closely intertwined. You could see it in my classrooms, the way my youngsters blossomed when they could express themselves in their mother tongue and how the light went out when they had to listen to and speak in English.' To help them learn English, she drew on their natural aptitude for singing and taught them traditional English folk songs,

‘Mãori children are very strong musically and it was no problem for them to learn songs in English and get the words right. It came naturally. It was creative and the constant repetition in the songs helped them. Mind you the Mãori language is relaxed and the enunciation of vowels is more rounded and makes for a richer sound but when we sang songs like Strawberry Fair we couldn’t get it as crisp as the English speakers. So those were the challenges and the repetition helped them develop a skill in the language.’

Throughout the service Merimeri’s daughter, Margaret sat at the top of the coffin, her arms wrapped around the wood, holding it in an embrace. Sometimes she would bend her head and talk to her mother, stroke her face. Anne Salmond sat nearby, cross-legged upon the floor and was visibly emotional. She and Merimeri were very close. They met in the Anthropology department in 1964. Merimeri was teaching te reo and Anne was her student. 'There I came upon her ladyship,' said Merimeri fondly. 'She was a fantastic student... only 21 when she became a lecturer.' It was a 'long, enduring friendship' one that was cemented during the fifteen year campaign for a marae on campus.

10pm

We made it back to Kerikeri just an hour ago. This day has been so long and full, twelve hours in all, driving, up and down Te Hiku-o-te-Ika from the Waiora marae at Ngataki to the Te Reo Mihi marae and the Mareitu urupa at Te Hãpua and returning to the Waiora marae where the day had begun for the hãkari, the feast, where we sat at long trestle tables sharing food together. Throughout the day, as guests we were privileged to experience Mãori manaakitanga, a most marvellous display of Maori hospitality. Just before the big drive back from Te Hapua to Ngataki, the mourners were given food, from the back of a utility vehicle, parked on the road outside the urupa; egg sandwiches and spring water with slices of lemon and from a box, we were offered yellow pears from someone's garden.

The tangi had begun three days earlier with the arrival of Merimeri’s body from Kaitaia to the Waiora marae at Ngataki. Over three days family, friends and colleagues had been gathering to remember and share the stories and to pay their respects. These are my impressions of the final day: The female minister spoke of aroha and how Merimeri had so much to give. She spoke warmly too of the mokopuna, about nurturing them and helping the children find their place to stand, their türangawaewae, the place where they feel especially empowered and connected. She urged the men, the kaumātua, to go into schools and say to the principal “I’m here to talk to the young people”. She urged them to 'Inspire the children and guide them.' At the end of this first service, smiling brightly she said, ‘Oh dear where did all those words come from. I think it was Merimeri speaking through me.’

When I asked Merimeri to talk about the meaning of home she said it is not the physical home that matters, it is the family and maintaining connection between members of the whãnau that matters. ‘…keep your family ties strong and get in their way if you have to. Whatever you do, stay close. I never know whether my family want me or not but my philosophy is to participate in family life.’ She went on to say that when her daughter’s child was unwell she stepped in to help.

‘I literally carried him on my back for the first three years of his life to relieve him and support his mother. They were seriously considering me as Dominion President of the Maori Women’s Welfare League. It was a great position. Later they asked, ‘Why did you disappear from the scene you could have been Dominion President?’ She told them her commitment was to the family and she never regretted the decision, ’When you do that sort of thing, it strengthens you. It strengthens you and it doesn’t run you down.’

Today I observed the children at the marae and the urupa; little boys with tee shirts illustrated with cartoon characters, Rey Mystique and Nirvana, standing quietly in the sun holding flowers in a kete - no scuffling, no noise, no fidgeting. I have never seen such well-behaved children in all my life. They know the etiquette. I noticed too older sisters, fathers and grandfathers with toddlers in their arms. Some of the little ones were asleep, their limbs relaxed and floppy - cherished children. It hurt Merimeri to view the negative constructions of Mãori and their relationship to children on the six o’clock news. She was offended by the film Once Were Warriors and its bleak focus on the disturbed, dysfunctional aspects of the lives of gang families, people who are cut off from their roots, lives wrecked by alcohol and drugs. Child abuse happens in Pãkehã culture as well, but isn’t emphasized in the media in the same way. 'There was no hope in that film, it was destructive,' she said. 'The only positive that I remember was when they went into the marae and I saw the Mãori element that was healing. That girl looked at the marae and she felt safe there. It didn't say much and was only a small part of the film.'

When the formal speech making, the whaikorero, began and people stood and recounted the stories one of the themes was Merimeri’s gentle influence and how it rippled beyond her whãnau, to all the people she came in contact with through the workplace and the academy right out into the culture. There were people from the University of Auckland and the University of Victoria, from Mãori television and the Human Rights Commission and there were students and friends gathered there too. Merimeri was remembered in their speeches for making her mark through teaching the Mãori language and raising awareness of Te Ao Mãori across the campus. Her stamina and resilience were remarked upon too. For fifteen years she campaigned with Anne Salmond and Pat Hohepa for a marae on the university grounds. The Waipapa marae would function as a learning environment to teach marae protocol to students. It would be a place to formally welcome visitors to the university and it would attract Mãori students to academic study. When the marae project was achieved, Merimeri and fellow campaigners brought pressure to bear on the university to create a separate Mãori Studies department because until then Mãori studies had been taught within the department of Anthropology. In her eighties Merimeri was still bringing Mãori ritual into the graduation ceremonies at Auckland University by performing the karanga, in her beautiful voice, to welcome the students who were graduating. To hear her call would raise the hairs on your neck.

Being at a tangihanga a person receives an immersive experience in Maori culture. There were times when listening to the oratory and observing the graceful interpolation of speeches followed by waiata when it felt as though the present moment existed outside of time. I was conscious of the deep reach of history and the whaikorero linking back to ancient traditions established well before European contact. When Mãori sing waiata, the male and female voices meld into glorious harmonies and the music moves in waves, layer upon layer of rich, melodious sound swelling up to the rafters. I remember Merimeri talking about her experience teaching Mãori children in the 1940s in remote schools in the central North Island; Upper Minginui Forest Primary School in Tühoe country, Te Whaiti Primary School near Ruatahuna, the Rãtana Pã in Wanganui and Poroporo Primary School in Whakatãne. She believed you needed to build on their strengths and give them a positive experience and so she always addressed them in Mãori even though the language was banned from classrooms at that time. 'When you suppress the language, you suppress the culture because the two are closely intertwined. You could see it in my classrooms, the way my youngsters blossomed when they could express themselves in their mother tongue and how the light went out when they had to listen to and speak in English.' To help them learn English, she drew on their natural aptitude for singing and taught them traditional English folk songs,

‘Mãori children are very strong musically and it was no problem for them to learn songs in English and get the words right. It came naturally. It was creative and the constant repetition in the songs helped them. Mind you the Mãori language is relaxed and the enunciation of vowels is more rounded and makes for a richer sound but when we sang songs like Strawberry Fair we couldn’t get it as crisp as the English speakers. So those were the challenges and the repetition helped them develop a skill in the language.’

Throughout the service Merimeri’s daughter, Margaret sat at the top of the coffin, her arms wrapped around the wood, holding it in an embrace. Sometimes she would bend her head and talk to her mother, stroke her face. Anne Salmond sat nearby, cross-legged upon the floor and was visibly emotional. She and Merimeri were very close. They met in the Anthropology department in 1964. Merimeri was teaching te reo and Anne was her student. 'There I came upon her ladyship,' said Merimeri fondly. 'She was a fantastic student... only 21 when she became a lecturer.' It was a 'long, enduring friendship' one that was cemented during the fifteen year campaign for a marae on campus.

Anne Salmond and Merimeri Penfold, 2009 by Gil Hanly

Anne Salmond and Merimeri Penfold, 2009 by Gil Hanly

On the night that Anne heard of Merimeri’s death she said she was writing out Merimeri’s first haka, written in 1976 at the time of the All Black tour to South Africa. The Mãori Women’s Welfare League had brought an anti-apartheid campaigner, Judith Todd, to New Zealand to speak to the League in Auckland about the situation in South Africa. Previously because of apartheid policies that barred indigenous people from participating in sport in South Africa, Mãori rugby players had been excluded from the All Blacks team but this time they were going too. Merimeri and her fellow campaigners felt the men should make a stand against racism and not go. It was then that Merimeri wrote her haka,

‘Me, be an honorary white… never, never, never!’ And I used two swear words in Mãori in this haka. “I shall bare my chest to the sun and be blackened!” Because it [the apartheid regime] was a monster we were dealing with, the devil we were dealing with. Afterwards, an elder – it was Matiu Te Hau – came and said, ‘You know, women don’t write haka. It’s for men, us men!’ And, he asked me, ‘When did you write this?’ I had written it the night before. I was stirred up so I woke up and wrote this thing. I said, ‘You know what? I wrote it when you were asleep!’ Merimeri laughed as she remembered this. She said that being a woman wasn’t important, it was the idea that mattered. ‘"You men want to be honorary whites in order to be entitled to travel." And, he said, "Well, let’s get away from that." And I said, "You don’t treat this seriously, you’re just messing around."’ It was male territory that I’d entered but you know, when issues like that come up, it’s no longer male territory. I felt strongly about it, enough to challenge the ‘menfolk.’

The tangi drew to its conclusion in Te Hãpua when the mourners followed the hearse up the hill to the Mareitu urupa for the burial. Up there at the northern most burial ground in New Zealand, on the hill above the Pãrengarenga Harbour, is a view to make your heart leap. Looking over the water, your eye is taken to a bar of pure white silica sand that divides the harbour from the Pacific ocean on the other side. Merimeri’s childhood home was sited on this hill and she remembered this view fondly,

‘It was on the top of a hill and looked down to the Pãrengarenga Harbour. It is a beautiful view. There is a bar of white silica sand on the headland opposite where the water drains out into the open sea. It’s a huge body of water, which fingers its way right into the hinterland.’ She described the water as very clean, a ‘nursery for fish’ and said that from their home they had a lookout and could ‘see people coming and going down on the flat. And we’d call out, "Is the tide coming in or going out?" because if it was going out then it was time for fishing.’

I have never seen anything so lovely at a graveside. The grave was lined with green ponga fronds and the mourners selected flowers from woven flax ketes to drop into the grave. I chose a crimson dahlia with a honeycomb pattern thinking of Merimeri and her mother’s love of flowers and also of taking tea at Merimeri’s home in Te Atatu when we were editing the transcripts. She served the tea in Royal Albert china edged with gold and patterned with pink roses. The flowers fell upon the coffin like pink and red rain amongst the green fern walls.

When I asked Merimeri for her thoughts on death and dying and the Mãori view of death. She said this:

We believe that our ancestors are waiting. In our farewell messages we write that we are following the path our ancestors have trod before us and we will follow as sure as day follows night, we will be following you. We accept this idea of the continuum. It prepares one psychologically for the eventual end in this world and I think it gives you a healthy frame of mind. I accept death and bide my time until I walk down the path of Tane. That’s the way it is going to be.

She also said that traditionally her people were not buried, ‘They were often sent down into a ravine that was inaccessible, or the body was put in some high, lofty place, and later the bones were recovered and painted with ochre and placed in a cavern. That was all that was required.’ When she died she said she didn’t want a gravestone, ‘just a simple plaque so people can find out where I am. That’s all I want.’ And she added ‘Actually I don’t have an expectation of even being remembered, really. That process is for each individual who was involved with me.’ At the grave today Merimeri’s daughter addressed her mother, “Mum we are burying you here at the urupa because our family needs a place to come where we can talk to you and remember you.’ And standing there in the sunshine and clear air of this most beautiful of final resting places at the very top of New Zealand, just below Spirits Bay where the spirits take their leave, it seemed entirely appropriate that a wahine toa from Te Hãpua should be buried here.

Post script: After I had finished writing this tribute to Merimeri I read again her words in Her Life’s Work and re-discovered these thoughts on the significance of the urupa at Te Hãpua:

When I go home to Te Hapua I always visit our cemetery because that’s where our relations are buried. It’s up on the hill and I look down on the same view that you can see from our old homestead, and that’s a very heartening experience. We always, all of us, when we go back home head straight up to the cemetery and have a chant or wish, and we talk.

‘Me, be an honorary white… never, never, never!’ And I used two swear words in Mãori in this haka. “I shall bare my chest to the sun and be blackened!” Because it [the apartheid regime] was a monster we were dealing with, the devil we were dealing with. Afterwards, an elder – it was Matiu Te Hau – came and said, ‘You know, women don’t write haka. It’s for men, us men!’ And, he asked me, ‘When did you write this?’ I had written it the night before. I was stirred up so I woke up and wrote this thing. I said, ‘You know what? I wrote it when you were asleep!’ Merimeri laughed as she remembered this. She said that being a woman wasn’t important, it was the idea that mattered. ‘"You men want to be honorary whites in order to be entitled to travel." And, he said, "Well, let’s get away from that." And I said, "You don’t treat this seriously, you’re just messing around."’ It was male territory that I’d entered but you know, when issues like that come up, it’s no longer male territory. I felt strongly about it, enough to challenge the ‘menfolk.’

The tangi drew to its conclusion in Te Hãpua when the mourners followed the hearse up the hill to the Mareitu urupa for the burial. Up there at the northern most burial ground in New Zealand, on the hill above the Pãrengarenga Harbour, is a view to make your heart leap. Looking over the water, your eye is taken to a bar of pure white silica sand that divides the harbour from the Pacific ocean on the other side. Merimeri’s childhood home was sited on this hill and she remembered this view fondly,

‘It was on the top of a hill and looked down to the Pãrengarenga Harbour. It is a beautiful view. There is a bar of white silica sand on the headland opposite where the water drains out into the open sea. It’s a huge body of water, which fingers its way right into the hinterland.’ She described the water as very clean, a ‘nursery for fish’ and said that from their home they had a lookout and could ‘see people coming and going down on the flat. And we’d call out, "Is the tide coming in or going out?" because if it was going out then it was time for fishing.’

I have never seen anything so lovely at a graveside. The grave was lined with green ponga fronds and the mourners selected flowers from woven flax ketes to drop into the grave. I chose a crimson dahlia with a honeycomb pattern thinking of Merimeri and her mother’s love of flowers and also of taking tea at Merimeri’s home in Te Atatu when we were editing the transcripts. She served the tea in Royal Albert china edged with gold and patterned with pink roses. The flowers fell upon the coffin like pink and red rain amongst the green fern walls.

When I asked Merimeri for her thoughts on death and dying and the Mãori view of death. She said this:

We believe that our ancestors are waiting. In our farewell messages we write that we are following the path our ancestors have trod before us and we will follow as sure as day follows night, we will be following you. We accept this idea of the continuum. It prepares one psychologically for the eventual end in this world and I think it gives you a healthy frame of mind. I accept death and bide my time until I walk down the path of Tane. That’s the way it is going to be.

She also said that traditionally her people were not buried, ‘They were often sent down into a ravine that was inaccessible, or the body was put in some high, lofty place, and later the bones were recovered and painted with ochre and placed in a cavern. That was all that was required.’ When she died she said she didn’t want a gravestone, ‘just a simple plaque so people can find out where I am. That’s all I want.’ And she added ‘Actually I don’t have an expectation of even being remembered, really. That process is for each individual who was involved with me.’ At the grave today Merimeri’s daughter addressed her mother, “Mum we are burying you here at the urupa because our family needs a place to come where we can talk to you and remember you.’ And standing there in the sunshine and clear air of this most beautiful of final resting places at the very top of New Zealand, just below Spirits Bay where the spirits take their leave, it seemed entirely appropriate that a wahine toa from Te Hãpua should be buried here.

Post script: After I had finished writing this tribute to Merimeri I read again her words in Her Life’s Work and re-discovered these thoughts on the significance of the urupa at Te Hãpua:

When I go home to Te Hapua I always visit our cemetery because that’s where our relations are buried. It’s up on the hill and I look down on the same view that you can see from our old homestead, and that’s a very heartening experience. We always, all of us, when we go back home head straight up to the cemetery and have a chant or wish, and we talk.