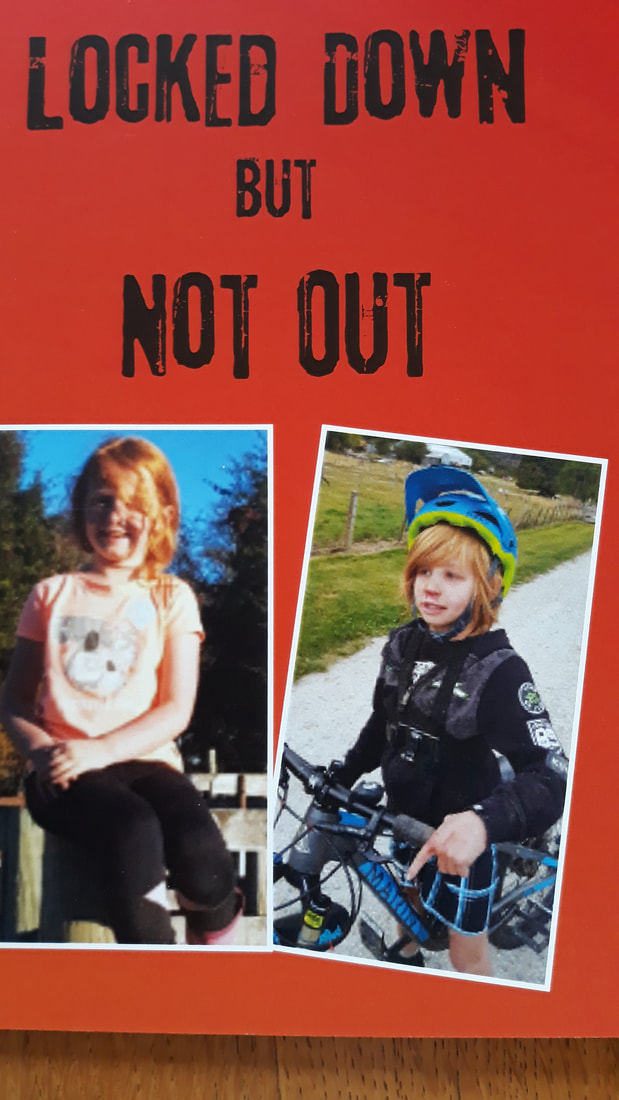

In the time of coronavirus

A collection of stories submitted by the public on their experience of living through the time of the Coronavirus pandemic.

|

The coronavirus pandemic has changed our lives. Globally the scale of human suffering as a consequence of Covid-19 has been very great. Everywhere people are now reflecting on what this major and previously unimaginable global crisis means for us, as individuals, living in the 21st century. This forum offers a space for writers to reflect on their experience in Aotearoa and to consider questions such as: What might we need to remember and preserve? What has been my experience, my observations, how might my priorities have shifted, in a good way, as a result of the lockdowns? If you would like to contribute to the re-collective effort through any of the following life writing formats — journalling, nature writing, memoir, commentary, poetry, notes on work in progress during lockdown… — please make initial contact through my contact page. Next prepare a page of A4 writing, starting in the present moment and moving where you need to into the recent past and forwards from that point, with a title, brief bio, photo (optional) and your contribution will be added to the repository of important writings flowering in this space.

“Securing the memory of COVID-19 is the minimum we owe to each other in the aftermath of this catastrophe.” Richard Horton, “Covid-19 and the Ethics of memory", The Lancet , 6 June 2020 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed