|

Debbie, having left full time work as an academic, now has a new day job - to record her parents’ story for their grandchildren and great grandchildren. Her biggest regret is not having had the interest, when they were still alive, to talk to her parents and aunties and uncles more about their lives while she still could. Fortunately, she now has the time to research her parents’ story, and her ancestry, and actually get down to capturing her findings on paper. The first project is on her father.

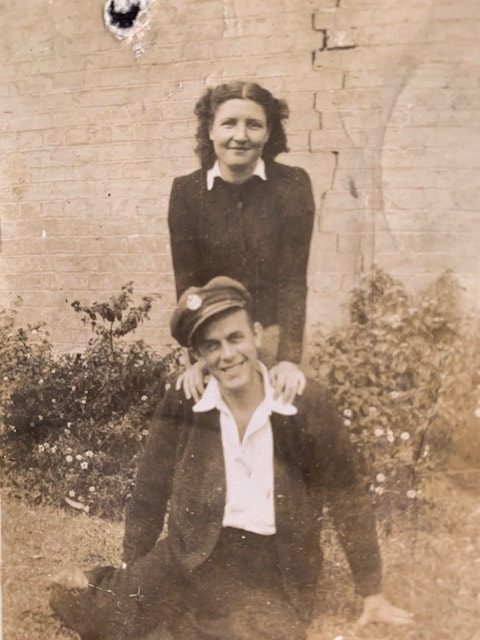

It all started with the discovery, during a decluttering exercise, of my father’s medals that had been casually tossed in a drawer. “Do you know what we have here?” exclaimed my (late) husband Mike, after googling them. “This one is the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). It’s one down from the Victoria Cross, and awarded to non-officers, for outstanding bravery.” I knew that Dad, Flight Sergeant Ralph James Hardy, had been a prisoner of war under the Japanese in Hong Kong, that he worked in labour gangs on the extension of the Kai Tak airfield, and had been involved, along with a group of POWS, in smuggling messages in and out of the camp. In July 1943, they were betrayed, tortured and tried. Three of the senior officers were sentenced to death by execution, and my father, along with two others, were sentenced to fifteen years hard labour and sent to a jail in Canton (Guangzhou). I knew there were medals but hadn’t appreciated the real significance behind the DCM. Suddenly things I’d heard growing up, came into focus. There were family stories that ‘young Ralph’ had been a bit of a rascal, a dare-devil with a penchant for taking risks, much to the despair of the local community bobby, who unknowingly, when he said more than once “That boy will either end up in jail or Buckingham Palace” was right on both accounts. My father, though a scholarship boy, had to leave school at fourteen to keep his brother at university. He joined the RAF in 1937 at the age of twenty, seeking more education and better prospects. He was posted to Hong Kong where he met my mother Hazel Frances O'Sullivan. Their courtship was interrupted by the fall of Hong Kong and they didn’t marry until after the liberation. Had they married earlier my mother, an Irish national, would have been interned as well. Throughout the war and his imprisonment, my mother took risks smuggling messages and food to him and other POWs. Afterwards she was known for her deeds as “The Angel of Hong Kong.” In my possession are a collection of photographs, and a bundle of letters, written on card, tied up with a pink ribbon, that Dad wrote to Mum, his “Darling Spuds” from the POW camp in Hong Kong. I didn’t know until recently, that somewhere in those love letters, there were also coded messages that I now need to decipher. It was my husband who set me on the path to reconstruct my father’s life. Now that he is gone I am continuing the project hoping to capture the story of how a bright working class boy from Yorkshire survived unimaginable conditions (torture, beatings, solitary confinement and the constant threat of death) in the prison camp, went on to become a proven linguist as an examiner of Cantonese, Mandarin and Hakka Chinese languages, and to have a highly successful career as the Registrar of Trade Unions in Hong Kong. On retirement he was awarded another medal, The Imperial Service Order, for his “faithful service”, received from the Queen Mother at an investiture ceremony at Buckingham Place. I am writing to honour his life and also the role my mother played in it. Comments are closed.

|

Your StoriesPlease submit your story via the Contact page and it will receive a gentle edit from Deborah.

Authors

All

Archives

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed