Marti Friedlander

19 February 1928 - 14 November 2016

Today I attended a funeral service at the Waikumete Cemetery to honour the life of Marti Friedlander. It was a simple service held in a small wood-lined chapel shaped like a Star of David in the Jewish section of the vast graveyard. The wind swirled outside as we listened to the rabbi reciting the Hebrew prayers and blessings, and to the eulogy by Leonard Bell, art historian, gallery curator, author and good friend of Marti Friedlander, such an intelligent mapping of her life path and career highlights, full of heart and warmth and made very poignant by quotations from a letter written by Marti’s 90 year old sister who lives in London. It was Anne who had been a comforting presence in Marti’s life, from the time they arrived in London, frightened little orphans from the war in Poland, and through the years they spent at the orphanage and right up until and beyond the moment that Marti met her future husband Gerrard Friedlander and emigrated to New Zealand.

At the conclusion of the service the pallbearers carried the coffin up the sloping hill to the grave and we watched as first Gerrard, the great love of her life, her devoted companion, her rock, and then the family, and then one by one the mourners scooped clay from a huge mound of freshly excavated soil into the grave, on and on digging, thrusting, standing aside for the next person to take over getting the job done. And I thought, standing there in the whirling wind, amongst the huge gathering of mourners, how practical was this practice and cathartic.

At the conclusion of the service the pallbearers carried the coffin up the sloping hill to the grave and we watched as first Gerrard, the great love of her life, her devoted companion, her rock, and then the family, and then one by one the mourners scooped clay from a huge mound of freshly excavated soil into the grave, on and on digging, thrusting, standing aside for the next person to take over getting the job done. And I thought, standing there in the whirling wind, amongst the huge gathering of mourners, how practical was this practice and cathartic.

Self-portrait, 1978, Marti Friedlander (AUP)

Self-portrait, 1978, Marti Friedlander (AUP)

There were so many people gathered on the hill — Marti would have been pleased — her family, people from the Jewish community, the arts community, the writers; the author C K Stead, whose unforgettable portrait, framed in extreme close-up, of his lined and furrowed face, was produced by Marti for the cover of his book Collected Poems (2009); and the photographer Gil Hanly still faithfully recording all the momentous events in our cultural and political landscape; and the film making partnership Shirley and Roger Horrocks whose film Marti: A Passionate Eye (2004) provides a compelling portrait of the photographer. The footage they captured of Marti, her brightly animated pixie face speaking direct to camera, is a taonga for the people of Aotearoa, to remember her by because Marti was an intrepid, energetic and dynamic figure, an artist who shook up the culture. When she arrived in New Zealand, from the bohemian and arts environment of London, she looked aghast at what seemed a culturally barren wasteland. Leonard Bell used the phrase ‘the passionless people’ from the book by Gordon McLauchlan, in his eulogy to describe the timbre and conservatism of the populace she encountered. And so she set to work and produced her portraits of New Zealanders, revealing and fostering another more vital strand of the nation and its people, the artists and writers and thinkers, the protesters and activists and in 1979 she collaborated with Michael King on the very special book, Moko: Maori Tattooing in the 20th Century and produced a series of portraits that today provide a precious and profound record of Maori kuia from that era.

Epilogue

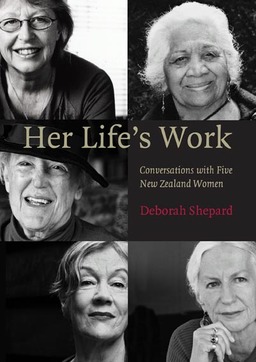

Her Life’s Work: Conversations with Five New Zealand Women (AUP, 2009)

Her Life’s Work: Conversations with Five New Zealand Women (AUP, 2009)

When I was completing my book Her Life’s Work (2009) about Jacqueline Fahey, Margaret Mahy, Merimeri Penfold, Gaylene Preston and Anne Salmond I asked photographer Marti Friedlander if I could write about her involvement in the project and feature it as an epilogue following the final chapter. I wanted to record Marti’s significant contribution. Her stunning portraits of the five women, all of which exude great poise and beauty, provided the essential and compelling visual dimension to my text, giving the women the mana they deserved. I wanted to pay tribute to Marti in this way because originally I had hoped that Marti would feature in the book as well but she had decided no. She’d not so long ago been the topic of Shirley Horrock’s documentary and there was another book in production, Marti Friedlander (2010) by Leonard Bell with a foreword by writer Kapka Kassabova and Marti thought that was enough for now. But sensing my disappointment she immediately made an offer, ‘I would love to photograph the women, Deborah.’

Below is the excerpt from Her Life’s Work with an account of the process that transpired.

Below is the excerpt from Her Life’s Work with an account of the process that transpired.

It was an education to work with Marti Friedlander. From the very beginning she was clear about her process. She would liaise directly with each of the five women and go alone to the portrait sessions. She would also be in charge of the selection process and choose the final print for publication. Her stylistic emphasis nowadays, she said was on lean simplicity, paring back to the person’s essence, taking the artist out of the living and working environment insisting on no make-up or jewellery, no extraneous details.

So I followed Marti’s directions and stayed away from each shoot. But on the day the individual women occasionally influenced the final result and sometimes practicality dictated a different approach. Merimeri wore her pounamu pendant, her paua pin brooch and drop earrings. Jacqueline wore her bright red lipstick but she did, at Marti’s bidding take off her earrings, and was not entirely pleased about that. Gaylene’s photograph was taken in Marti’s home on the day that Gaylene filmed Marti for her documentary Lovely Rita (2007) about the artist Rita Angus. That portrait records Gaylene, the film director, relaxed and in command of her own process on that day. For Anne Salmond the rules were relaxed. Marti had photographed Anne years earlier with Amiria Stirling and Anne’s baby daughter, Ami and this portrait session was a warm reunion. Perhaps Anne influenced the final setup as she is very much at home in her own environment sitting at her desk with her papers to the side and her laptop and book, Amiria: A Tribal Elder, are in the foreground.

On Margaret Mahy’s shoot, however I got lucky and did at last have a chance to see Marti at work when I accompanied her to Christchurch and drove her over the hill to Margaret’s home in Governors Bay.

We arrived on a brilliant autumnal morning, the air crisp, the light sharp and clear, just right, Marti said for a photographic shoot. As we pulled into the driveway we spied Margaret crossing the drawbridge to her front door carrying a bundle of wood. Inside, over coffee and pastries, in front of a crackling fire, Marti and Margaret talked about their lives. They had never previously met yet the connection and mutual liking was instant.

As they talked I could see Marti assessing the light and the environment. Her eyes scanned the room and the view up the harbour, the shelves of books and collections of dolls and pottery figures. Then she cast her photographer’s eye over Margaret who had had her hair set for the occasion. Marti decided to photograph Margaret in a black slightly dusty felt hat that fitted snugly on her head.

Marti tried several locations, always searching for the right light before settling on the ideal position. She photographed her on the mezzanine floor overlooking Margaret’s living room. She directed her outside to a small upper deck smothered in grapevine and positioned Margaret in the middle of the vine amongst tightly curling tendrils and baby grapes. Lyttelton Harbour and the Port Hills formed the background. I thought the arrangement looked tremendous but ‘No,’ said Marti. ‘The back lighting is too bright.’

In the living room Marti asked Margaret to perch on the top of a sofa and direct her gaze towards the big window with the harbour view. The light was softer there. Then Marti bent over the view-finder that sat up proud from the camera, concentrating. She directed Margaret to tilt this way and lean the other. She noticed Margaret’s hands. ‘Spread your fingers,’ she instructed, ‘I like your ring.’ Margaret was wearing what looked like a family heirloom, a well-worn ring set with large diamonds. Margaret was patient and amenable. ‘Close your mouth,’ said Marti and the mouth shut. ‘Smile. Now laugh.’ And Margaret laughed, a deep, rich bubble of sound welling up from inside. ‘That’s terrific,’ said Marti. Moving in closer for a head-and-shoulders shot she instructed, ’Now just hold it like that for me please,’ Marti pulled focus. ‘That’s good. That’s marvellous.’ And watching, I saw Margaret settle and soften and felt sure that would be the photo.

After the shoot there was time for another cup of coffee, and more conversation in front of the fire. Margaret was pleased with the session, ‘I’ve never seen a photographer work in this way with such attention to detail.’ They compared notes on ageing, Margaret commenting wistfully, ‘I wish I had your energy.’

Out on the shingle road, as we crunched through autumn leaves to the car, Marti noticed walnuts scattered there and suggested we gather some ‘for Gerrard’. Driving away, she said, ‘I think we’ve got some good shots. But don’t say anything. I never talk about it afterwards. We’ll wait for the proofs.’

I met Marti a month later at her favourite cafe in Parnell where she conducts her business meetings while Gerrard sits nearby reading the morning paper. There she presented me with the photo of Margaret Mahy in her felt hat near the big window, the fifth and final photograph for the book. Marti was leaving the next day on a three-week tour of Turkey, ‘God forbid, Deborah, if anything should happen to me or Gerrard while we’re away, well at least you’ve got your photos.’

Then, Marti leaned forward and looked at me, closely, as is her way. ‘And how are you Deborah?’ she asked. ‘My boy is 14 today and it feels like a milestone,’ I answered. Marti replied, ’If he were Jewish he’d have had a Barmitzvah at 13 to mark his coming of age.’ Marti talked now about the loss of her only child in 1963 during childbirth. ‘Gerrard and I have often wondered about our daughter. Of course you wonder, anybody would,’ she said. ‘Would she have been as beautiful as Gerrard? Would she have had my personality? We’ll never know and perhaps there’s no point in wondering. It’s all conjecture.’ Her tone was matter of fact.

I studied her then, she was wearing a pendant with an image of a Renaissance baby angel, bought at the National Gallery, over the soft charcoal linen shirt, she favoured. All eighty years of living seemed somehow written across her face – the orphanage beginnings, the travel, the photography, the constant reaching and overreaching for higher and brighter goals, the brilliance and the indomitable strength.

‘I let these things go,’ Marti was saying. ‘After all Deborah, if I’d been a mother I may not have been a photographer.’ This was indeed a powerful thought. ‘Of course I very much wanted to be a Mother, but it didn’t happen. I learned to accept what is from a very early age and have always tried to have a positive outlook in spite of sadness. I always knew I had to keep moving forward.’ Already Marti was pushing back her chair and preparing to make her way up Parnell Road to her next appointment.

After her departure I reflected on Marti and the five women in this book and it occurred to me that they each demonstrate a powerful way of being in the later years of a life, having an innate optimism and vitality, a zest for living that derives from remaining passionately involved in work that brings pleasure. I thought too how lucky I was to have been granted this opportunity to work with Marti Friedlander and to explore the life and work of all six women and be touched by them.

So I followed Marti’s directions and stayed away from each shoot. But on the day the individual women occasionally influenced the final result and sometimes practicality dictated a different approach. Merimeri wore her pounamu pendant, her paua pin brooch and drop earrings. Jacqueline wore her bright red lipstick but she did, at Marti’s bidding take off her earrings, and was not entirely pleased about that. Gaylene’s photograph was taken in Marti’s home on the day that Gaylene filmed Marti for her documentary Lovely Rita (2007) about the artist Rita Angus. That portrait records Gaylene, the film director, relaxed and in command of her own process on that day. For Anne Salmond the rules were relaxed. Marti had photographed Anne years earlier with Amiria Stirling and Anne’s baby daughter, Ami and this portrait session was a warm reunion. Perhaps Anne influenced the final setup as she is very much at home in her own environment sitting at her desk with her papers to the side and her laptop and book, Amiria: A Tribal Elder, are in the foreground.

On Margaret Mahy’s shoot, however I got lucky and did at last have a chance to see Marti at work when I accompanied her to Christchurch and drove her over the hill to Margaret’s home in Governors Bay.

We arrived on a brilliant autumnal morning, the air crisp, the light sharp and clear, just right, Marti said for a photographic shoot. As we pulled into the driveway we spied Margaret crossing the drawbridge to her front door carrying a bundle of wood. Inside, over coffee and pastries, in front of a crackling fire, Marti and Margaret talked about their lives. They had never previously met yet the connection and mutual liking was instant.

As they talked I could see Marti assessing the light and the environment. Her eyes scanned the room and the view up the harbour, the shelves of books and collections of dolls and pottery figures. Then she cast her photographer’s eye over Margaret who had had her hair set for the occasion. Marti decided to photograph Margaret in a black slightly dusty felt hat that fitted snugly on her head.

Marti tried several locations, always searching for the right light before settling on the ideal position. She photographed her on the mezzanine floor overlooking Margaret’s living room. She directed her outside to a small upper deck smothered in grapevine and positioned Margaret in the middle of the vine amongst tightly curling tendrils and baby grapes. Lyttelton Harbour and the Port Hills formed the background. I thought the arrangement looked tremendous but ‘No,’ said Marti. ‘The back lighting is too bright.’

In the living room Marti asked Margaret to perch on the top of a sofa and direct her gaze towards the big window with the harbour view. The light was softer there. Then Marti bent over the view-finder that sat up proud from the camera, concentrating. She directed Margaret to tilt this way and lean the other. She noticed Margaret’s hands. ‘Spread your fingers,’ she instructed, ‘I like your ring.’ Margaret was wearing what looked like a family heirloom, a well-worn ring set with large diamonds. Margaret was patient and amenable. ‘Close your mouth,’ said Marti and the mouth shut. ‘Smile. Now laugh.’ And Margaret laughed, a deep, rich bubble of sound welling up from inside. ‘That’s terrific,’ said Marti. Moving in closer for a head-and-shoulders shot she instructed, ’Now just hold it like that for me please,’ Marti pulled focus. ‘That’s good. That’s marvellous.’ And watching, I saw Margaret settle and soften and felt sure that would be the photo.

After the shoot there was time for another cup of coffee, and more conversation in front of the fire. Margaret was pleased with the session, ‘I’ve never seen a photographer work in this way with such attention to detail.’ They compared notes on ageing, Margaret commenting wistfully, ‘I wish I had your energy.’

Out on the shingle road, as we crunched through autumn leaves to the car, Marti noticed walnuts scattered there and suggested we gather some ‘for Gerrard’. Driving away, she said, ‘I think we’ve got some good shots. But don’t say anything. I never talk about it afterwards. We’ll wait for the proofs.’

I met Marti a month later at her favourite cafe in Parnell where she conducts her business meetings while Gerrard sits nearby reading the morning paper. There she presented me with the photo of Margaret Mahy in her felt hat near the big window, the fifth and final photograph for the book. Marti was leaving the next day on a three-week tour of Turkey, ‘God forbid, Deborah, if anything should happen to me or Gerrard while we’re away, well at least you’ve got your photos.’

Then, Marti leaned forward and looked at me, closely, as is her way. ‘And how are you Deborah?’ she asked. ‘My boy is 14 today and it feels like a milestone,’ I answered. Marti replied, ’If he were Jewish he’d have had a Barmitzvah at 13 to mark his coming of age.’ Marti talked now about the loss of her only child in 1963 during childbirth. ‘Gerrard and I have often wondered about our daughter. Of course you wonder, anybody would,’ she said. ‘Would she have been as beautiful as Gerrard? Would she have had my personality? We’ll never know and perhaps there’s no point in wondering. It’s all conjecture.’ Her tone was matter of fact.

I studied her then, she was wearing a pendant with an image of a Renaissance baby angel, bought at the National Gallery, over the soft charcoal linen shirt, she favoured. All eighty years of living seemed somehow written across her face – the orphanage beginnings, the travel, the photography, the constant reaching and overreaching for higher and brighter goals, the brilliance and the indomitable strength.

‘I let these things go,’ Marti was saying. ‘After all Deborah, if I’d been a mother I may not have been a photographer.’ This was indeed a powerful thought. ‘Of course I very much wanted to be a Mother, but it didn’t happen. I learned to accept what is from a very early age and have always tried to have a positive outlook in spite of sadness. I always knew I had to keep moving forward.’ Already Marti was pushing back her chair and preparing to make her way up Parnell Road to her next appointment.

After her departure I reflected on Marti and the five women in this book and it occurred to me that they each demonstrate a powerful way of being in the later years of a life, having an innate optimism and vitality, a zest for living that derives from remaining passionately involved in work that brings pleasure. I thought too how lucky I was to have been granted this opportunity to work with Marti Friedlander and to explore the life and work of all six women and be touched by them.