|

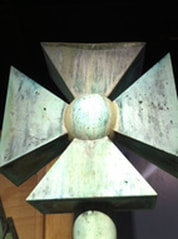

Recently I reread my earlier entries and considered my raw responses, following the catastrophic earthquakes in Canterbury and decided I still stand by these pieces. It is tempting as a writer, who also edits the work, to want to make changes and to worry. Was the writing too emotional, partial, profuse? Was I writing out my distress? Probably. But I also think a writer needs to hold a position and that the style should somehow transmit the flavour of the person, her interests and passions, otherwise why bother to write. I also see these outpourings as the essential work of a life writer, writing in the midst of extraordinary life events, articulating thoughts and feelings, reflecting, remembering and documenting for the records. When I revisited Christchurch at Queen’s Birthday weekend, I wondered whether this time I might write more optimistically about the changes in the city. A huge amount of human effort has poured into the city in the last year. The engineers, geologists and scientists are making it a safer place. The architects and designers are working to re-create a fully operational and hopefully beautiful city. The artists and curators are responding creatively in very trying conditions and producing works of great power and meaning. This time I planned on seeking out the positive developments, taking a closer look at the gap filler projects while staying true to my feelings. The weekend began with a visit to a touring exhibition, curated by the Natural History Museum, London, of Captain Robert Scott’s expedition to the South Pole in 1912, and currently on show at the Canterbury Museum. This is a building I have been keen to revisit for it is one of the few remaining Gothic Revival buildings in the city that appears to have survived the quakes largely intact. It was designed by Victorian Gothic architect, Benjamin Mountfort and completed in 1882. His Great Hall across the road at the Arts Centre also survived and is currently undergoing major restoration. Walking through the museum I found the model Christchurch street remembered from childhood, exactly as I remember it —the blacksmith’s forge and the shoe shop displaying peach and cream satin shoes, a little like ballet slippers with small buttons on the side. The toyshop, round the corner is as I remember it with its porcelain dolls, their painted blue eyes staring blankly, and the room with the collector’s treasure trove is still packed with stuffed and scary animals including an enormous elk skeleton with big antlers like tree branches. The dioramas illustrating Maori life before the arrival of Pakeha were the exhibits that fascinated me as a child. They were very beautifully executed with slightly smaller than life-size models of men hunting and trapping animals and birds in the bush, or out on the Canterbury marshes or in the bays on Banks Peninsula. Featured against eggshell-blue skies and amongst the olive-green native bush they hunt Moa, they roast mutton-birds on the beaches, while the women are weaving kete and cloaks… As I admired the feathery beauty of real Kiwi pecking for pretend grubs in the foreground, I felt a sense of relief. There has been no modernisation of the museum in this respect, and that is a comfort in these strange times.  2. Illustration of Scott sculpture 2. Illustration of Scott sculpture The Scott Exhibition begins arrestingly with the explorer’s larger than life-size statue lying horizontal and broken on a plinth like a mighty giant fallen. In the earthquake his feet were sheared off as the statue fell. The exhibition notes inform the reader that Scott’s wife Kathleen Bruce/Scott sculpted the statue following his death. She had trained at the Slade School of Art in London (1900 – 1902) and the Academie Calarossi (1902 – 1906) in Paris. Six years of training and it shows in the magnificently executed sculpture, the dramatic rippling marble folds of cloth. Kathleen Scott was an interesting woman, strong and determined, she wrote loving letters to Scott when he was away. She was also a very enchanting creature in a Pre-Raphaelite way. She wore her wavy long hair free and flowing. Apparently she urged Scott to make the expedition to the South Pole and be the first explorer to do so. Her letter was found in his breast pocket after his death; “We can do without you . . . if there be a risk to take or leave, you will take it.” Scott did reach the pole but was beaten by the Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen, by one month. and Scott and his expedition companions failed to return They died from exposure just eleven miles out from a hut that would have saved them. On Scott’s expedition, he took with him a band of twelve clever men; two biologists, three geologists, a physicist, a meteorologist, a medical doctor who was also a research zoologist, and the expedition was documented by the photographer Herbert Ponting. These men stayed behind at the base hut at Cape Evans and conducted scientific research, pushing forward human understanding of glaciology and geology, as they pursed a greater understanding of the lifecycles of the various species that inhabit Antarctica. They collected over 40,000 specimens representing over 2000 animals and plants, 400 of them previously undiscovered. In a true-to-scale recreation of the hut at Cape Evans there is a replica of the large table around which the men sat drawing their maps and diagrams, sketching their illustrations, dissecting an emperor penguin’s intestine, and eating their dinners.  3. Illustration of specimens gathered on the expedition 3. Illustration of specimens gathered on the expedition Scott’s last entry in his journal is deeply affecting because he knew, like Katherine Mansfield writing her final entry in her journal in October 1922, that his life was about to end: … For four days we have been unable to leave the tent – the gale howling about us. We are weak, writing is difficult, but for my own sake I do not regret this journey, which has shown that English men can endure hardships, help one another, and meet death with as great a fortitude as ever in the past. We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence, determined still to do our best to the last …[ii] I don’t know whether Scott was a religious man, but his surrender to the will of Providence, or the will of nature, is pertinent to the situation in Christchurch today. Here people have been reminded of the mighty power of nature and the tenuousness of human existence. At the end of the letter he writes; These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale, but surely, surely a great rich country like ours will see that those who are dependent on us are properly provided for.[iii] The ‘great rich country’ is of course England and the dependents are his wife and child Peter Scott - who later became a renowned British ornithologist, conservationist and painter of exquisite scenes of birdlife - and the families of his four expedition mates; the chief scientist Dr Wilson and Captain Oates, Lieutenant Bowers and Edgar Evans - who perished with him. There is currently, a discourse around the reconstruction of Christchurch, that focusses on budgetary constraint – which is reasonable in a recession - but unreasonable as an excuse to bulldoze the hell out of Christchurch and destroy most of its heritage fabric. This attempt to stall on decision-making over the restoration and re-build of major and important pieces of architecture and the homes of Christchurch citizens is concerning. I’m not an expert on the wealth of various countries, but I believe that we live in a ‘rich country,’ rich in cultural traditions certainly but there are big disparities between those with comfortable living standards and those ‘ who are dependent on us’ to be ‘properly provided for.’ Surely our country could do better for the families who have lost their homes and who are still, two and half years out from the quakes, living in caravans and garages. We could do better for people waiting on decisions that will allow them to resolve the fate of their wrecked homes and move forward. The situation is dispiriting and depressing. On this trip I noticed the sour smell of damp and liquefaction in homes and on the streets. When it rains in these areas mud pours down the gutters.  4. Illustration – the copper cross from the Basilica 4. Illustration – the copper cross from the Basilica In a shed-like building in the Cashel Mall there is an exhibition of broken treasures rescued from heritage buildings. I hadn’t realised, when I purchased my ticket, that the exhibition would be directed at the tourism market although a Christchurch friend remarked recently, ‘We are all tourists now, wandering like strangers around our city.’ I wasn’t prepared for the blow-up photographs of people on stretchers being carried, by Saint John Ambulance staff, away from fallen buildings on the day of the disaster. Fortunately we were warned about the three-minute film re-enactment of the earthquake and could avoid that room. The first treasure is the beautiful deep-blue copper cross from the main dome of the Basilica. This cathedral on Barbadoes Street, unforgettable for its stunning colours, the cream Oamaru stone juxtaposed against bright aqua copper domes is currently being de-constructed block by block. The most recent plan is to save the façade and the northwest wall as a relic, or an open-air ruin and to use the remaining stone for a new church. I do hope their wonderful intention can be realised as this would be healing. There was a maroon leather, father bear-sized chair, that had been the speaker’s chair in the Provincial Council Chambers. That building is still a wreck, but fortunately and thankfully there will be a rebuild, eventually. I saw the stencilled rafters from its lovely ceiling their ragged splintered edges speaking of the force of that terrific jolt on February 22nd. Scientists have used an analogy for the velocity of the seismic eruption, describing it as like a ‘supersonic boom of a jet aircraft’.  5. Illustration - Rafter 5. Illustration - Rafter The beautifully patterned Maori tukutuku panels woven from muka and dyed gold, maroon and cream that once hung in the Anglican cathedral are on display along with the straightened out silver spire that we saw crashing to the ground, on television news footage, that looped over and over driving us mad with grief and shock on February 22nd.  6. Illustration - Tukutuku panels 6. Illustration - Tukutuku panels The exhibit included a sample of the structural reinforcement used for restoring the few remaining churches and historic buildings, an arrangement of steel beams cemented to the main material, in this case grey stone. The information panel confirmed this technique will be used to restore the Gothic Revival stonework of the Holy Trinity Church on the corner of Worchester Street, behind the cathedral. I am glad about this. I sat my piano exams in that church, playing the music in the kaleidoscope of coloured light from the rose window. On an earlier visit to the city, there was a gaping hole where the rose window had once been and oddly the beautiful light fitting, four simple candle lights on brass arms, was still hanging in the gap under the dark-beamed pitched roof. There are so many questions still and sometimes the answers are not good. Since my last visit in January, the mesh fences have been pushed out from Ballantynes department store revealing a view to the edges of the square. You can’t walk into the square as yet – I got hollered at by a soldier when I drifted into the wrong part, trying to get a closer look at Neil Dawson’s silver and blue chalice. Perhaps that beautiful big sculpture echoing the colours in the sky will become the new icon of cathedral square.

Botanical Preservation Project seeks to find a balance between loss and memory, and appreciation of the here and the now. It has been done in memory of what has been, but more importantly it is a celebration of this moment and the possibilities of the future. Their growth alludes to a dynamic and evolving way we can see and engage with Christchurch as it rebuilds. Plants have taken root, without the need for human care, or permission and have provided us with a joyous and readily available marker of life. My mother-in-law says this happened in London and Europe after the war. Nature swept over the bombsites ‘healing the wounds.’  9. Illustration - Theatre Royal propped up 9. Illustration - Theatre Royal propped up Very few buildings remain in the city but thankfully there are some facades, eerily propped up with voids beyond. The samples of architecture, Gothic, Classical Revival and Victorian Arts and Crafts are pierced with steel rods that join them to stacks of colourful containers. These shapes look like toy building blocks in deep blues, turquoises, bright reds and oranges. The Theatre Royal next to New Regent Street is reinforced in this way, while inside it is undergoing a faithful recreation/restoration that incorporates the remaining façade. Meanwhile the large ceiling dome presently packaged in white plastic sits under a makeshift roof behind the facade.  10 Illustration - SAVE CHCH 10 Illustration - SAVE CHCH Some of the mesh fences in the central city are clad with children’s paintings: a little Maori boy with big white teeth and a speech bubble saying ‘SAVE CHCH by Kyle.’ Jack’s blue painting has a peace sign, and below that a large head with another speech bubble saying, ‘To the world man.’ One painting depicts five, blue, apartments, with little stick people in between, and green gardens, and the words ‘people people people!!! in the city.’ The painting underneath of two apartment buildings, black on pink has the words ‘GAP FILLER’, and ‘Hey Tangata, it’s people’.  11. Illustration - Margaret 11. Illustration - Margaret On the cream wall of one of the few surviving shops in the Cashel Street mall, the gallery has installed a portrait of, Margaret c.1936 by the Christchurch painter Elizabeth Kelly (1877 - 1946.) The artist first spotted Margaret Hatherley, at work in the department store, Beaths (now gone). She is very elegant in this portrait, in a dark navy dress, with a white belt around her slender waist, and a pink and red print scarf at her neck. Her elongated pale face is beautiful and a dark wavy bob hair cut. Her hands and fingers appear extraordinarily long. Surprisingly, for such a glamorous person she is holding a fishing tackle bag. The fishing rod leans against a luscious, folding cream curtain. And there she floats, enclosed in her photographed gilt frame, on view above our heads to be re-remembered and re-viewed by another generation of visitors to this astonishing open air exhibition. Over the three days of Queen’s Birthday weekend, the weather was tranquil. A nor’ west arch hung over the mountains making Canterbury look like scenes from art – Baroque, Neoclassical and like the paintings of Turner who is unclassifiable just his brilliant self, not belonging to an art movement. The banked up, pale blue clouds and yellow white sky reminded me of the paintings of Claude Lorrain. And the peculiar light, beaming intensely from under the clouds and making everything it touched brighter in colour and richer felt unreal as though we were walking through the facades and ruins of a neo-classical painting by Nicolas Poussin.  12. Illustration - City looking like Poussin 12. Illustration - City looking like Poussin On the last day I ventured beyond the city to the Eastern suburbs. I wanted to visit the beach at New Brighton and to re-experience the drive down Pages Road, to Hawke Street, where once, in another time, a great aunt and uncle lived at the end near the river, and at the other a diminutive great-grandmother, in a faded yellow dolls-sized cottage planted in the middle of a bank of sand covered in ice-plant, with a little sunroom on the front where she stored a long cardboard box with a collection of knitting needles and measuring devices that I liked to play with, poking the needles through the holes of the metal disks. To the left of Hawke Street, directly before Marine Parade, on Keppel Street, lived my grandmother and grandfather in a brick house with a porthole window in the bedroom. My grandmother bought a bunk so her grandchildren could climb the ladder and sleep in the top bunk next to the window. It had a wide shelf upon which to arrange my books and dolls. On this day, we drove along Marine Parade past the whale pool. The whale with its sad painted eyes is still there in its concrete pool swimming nowhere, trapped in a playground away from the beach. And some of the same houses I knew as a child are still present. I spied one cottage, very, very old, you can tell from the mix of board and batten and shingle patterning on the walls. Painted all over in a sea-soft turquoise colour it sat on a sand hill of ice-plant and agapanthus. There was a ‘For Sale’ sign at the front and I thought I might buy it but my husband thought this was a silly idea. Later, a friend said, ‘You could probably get it for three dollars.’ These eastern suburbs are sliding around on sand and silt. Some say these areas will eventually revert to marshland.  13. Turquoise house on iceplant illustration 13. Turquoise house on iceplant illustration I found the track, through marram grass and rabbit tails, the same track I’d scuttled over as a child with my grandmother. There was the same sea animated by endless rollers and same the stretch of beach over which I would run fast because the sand was very hot to hurtle myself into the fizzing surf. My grandmother stayed behind in the dunes - I knew where she was by the trail of cigarette smoke – and when I returned she would shake out a neatly rolled-up towel and hand me a basket with a bottle of Fanta, and a piece of fruit, and a handful of sweeties from a candy-striped bag from the pick ‘n mix section at Woolworths. Then together we would roast in the sun.  14. Illustration - Nor’ west arch 14. Illustration - Nor’ west arch On this afternoon, the light pouring from under a nor’ west arch over Pegasus Bay was radiant. In the space where the clouds joined the sky, the colour was pale egg yolk mixed with white while to the east, Brighton Pier was a light pencil sketch against Whitewash Heads in the far distance. There was no wind. Not a breath. The sea that will carry on turning for eternity barely made a noise as it broke on the sand. On the return trip we headed east and then turned right, near the estuary to face back towards the city. ‘Stop the car,’ I shrieked. We skidded to a stop. ‘What is it?’ ‘I have to get a photo. Look at the light!’ Nowadays I use my 21st century Iphone and the results are just okay, not brilliant but the phone is small and convenient. On this day it wouldn’t have mattered what device was pointed at the landscape, it was a transcendent moment. The image, I knew, would be breathtakingly beautiful. ‘We can go now,’ I said, satisfied. We’d only moved a few paces before I was pleading urgently to ‘take the right turn off the roundabout and STOP.’ Leaping out of the car I caught the low sunlight flooding the landscape with such brilliance, catching on native plants and grasses in the foreground and making the water in the pond a mirror reflecting perfect upside-down images of a bright blue-green crane and silver poles. And wait, in the middle of the pond a heron, slowly lifted and bent its elegant leg. Here again it was so silent I imagined hearing the small plishing sound of the heron’s movement. Above there was a whirring of ducks, the Grey Teal and the native bronze coloured Paradise Shelduck. It occurred to me then how the mighty seismic disturbances under Canterbury, that have wrenched at and distorted the ground, are an example of a nature that ‘taketh away,’ while here the watery pond and its bird-life are an example, mercifully, of a nature that ‘giveth back.’ This is the natural world and its healing power.  15. Illustration – cranes over bird sanctuary 15. Illustration – cranes over bird sanctuary Here again it was so silent I thought I could hear the small plishing sound as the heron dipped its foot into the water. I listened to the whirring flight of ducks, the Grey Teal and the little native bronzy coloured female Paradise Shelduck scudding in and fluttering out and felt grateful for the natural world and its healing power. It occurred to me that the mighty seismic disturbances under Canterbury that have wrenched at and distorted the ground in repeated blows are an example of a nature that ‘taketh away’ but here now amongst the growing things and the bird-life there is mercifully a nature that ‘giveth back’ and softens the wounds left by the earthquakes. [i] ‘Risk your life urged Captain Scott’s wife,’ Sunday Times, London, February 15, 2013 [ii] Captain Scott, Scott’s Last Expedition, Volume I, Wordsworth’s Classics of World Literature, London, 1913: 605 - 7 [iii] ibid. Comments are closed.

|

|